Review: How Coal Miners Fought the Railroad Barons

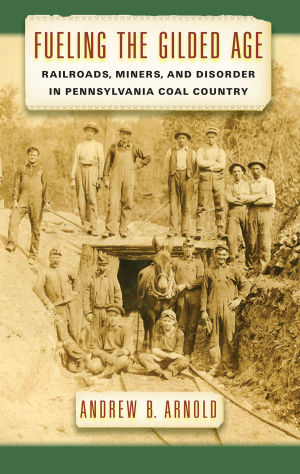

Fueling the Gilded Age: Railroads, Miners, and Disorder in Pennsylvania Coal Country, by Andrew Arnold, New York University Press, 2014.

Are you digging for a little historical inspiration? Want to uncover how workers struck against some of the world’s most profitable monopolies, using their leverage in a wildly profitable supply chain to demand a living wage—more than a century ago? You’ll find a rich seam in Andrew Arnold’s Fueling the Gilded Age: Railroads, Miners, and Disorder in Pennsylvania Coal Country.

Railroads were the conquering roadways of the late 19th century. Robber barons Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, and Cornelius Vanderbilt ran near-monopoly conglomerates that gave them enormous power to overrule the mine operators and set shipping rates for coal.

But taming the coal miners proved more difficult.

Birth of ‘Dues Check-off’

The last decades of the 19th century saw the Great Upheaval, a surge of labor organizing across the country—including in the Pennsylvania coal mines. The Knights of Labor promised a new, inclusive “Commonwealth of Labor,” bridging barriers of craft, class, and race.

Miners in Pennsylvania fought pitched battles to maintain their standard of living and autonomy on the job. With strikes, slowdowns, and marches through the community with a brass band, they resisted the mine owners’ efforts to speed up their work, since this would increase the risk of cave-ins, explosions, and asphyxiation by poisonous gas.

Court rulings based on Pennsylvania’s “free trade” regulations hampered the development of miners unions. And longstanding traditions of local community autonomy weakened their ability to organize statewide or region-wide strikes.

But union organizers found a way around the restrictive court rulings by negotiating “checkweighman” positions for each mine.

The checkweighman was responsible for double-checking the recorded weight of each miner’s load. Miners had long requested such a check, because of the operators’ perennial habit of short-weighing the load and cheating the miner out of his full wages.

Mineworker organizers formed checkweighman associations. They negotiated a wage to be paid the checkweighman, which the mine operator took out of all the miners’ wages. This was one of the country’s first “dues check-offs,” effectively binding every miner in the mine to the “association” as a paying contributor.

Some mine operators accepted the checkweighmen because they believed a statewide standard for payment per ton would stabilize the industry, stopping those operators who short-weighed from undercutting the common price.

From the checkweighman’s association, the union organizers gradually expanded to form a true union, the United Mine Workers of America.

Uneasy Partners

Meanwhile, mine owners organized the Seaboard Coal Association to combat the monopolistic power of the railroads.

Usually the operators joined forces with those same railroad companies to battle the growing union drive among the miners. But at times the mine operators and the miners found common cause.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Battling the railroad owners’ high shipping fees was in both groups’ interest. Lower shipping rates and a higher selling price for coal would have freed up funds to boost miners’ wages. Mine operators lost their fight with the railroads in the 1880s, however. As the railroads raised shipping rates, operators were pressured to lower wages.

Around the same time, the U.S. Supreme Court bestowed “personhood” on corporations, giving them broader legal authority than ever before. The court rulings limited the rights of the union to represent the rank and file and to bargain on their behalf.

Strike for a Living Wage

With strikes, slowdowns, and support from the Knights of Labor, the miners’ union grew in numbers and strength. But by the 1880s, rifts developed between the miners and the Knights.

The miners, still harboring a strong commitment to local autonomy, felt their organizational needs were not being met. The dispute grew into a raging battle. Many of the mine organizers were thrown out of the Knight of Labor.

The two sides finally came together, and the Knights agreed to grant the miners a high degree of autonomy. Now they had the daunting task of forming an effective national organization.

When striking miners in Punxsutawney called on their brother miners in eastern Pennsylvania to strike to support them, since both groups of mines were owned by the same company, at first the eastern men voted no.

But accused of “blacklegging” (scabbing on another mine), they went out on strike for higher, living wages, bolstering the reputation of the fledgling United Mine Workers of America.

Mine operators complained that they couldn’t afford to pay higher wages unless the shipping fees went down or the price of coal went up. The answer from the miners, a brash approach in its day, was to demand that wages be set by what miners needed to live—not by coal prices or shipping rates.

In effect, the miners were demanding a rise in the sale price of coal, in order to put food on their table and shoes on their children’s feet. And in many cases, they won.

Fueling the Gilded Age does a fine job of integrating the fierce competition among the railroad barons with the long, uphill fight to establish the United Mine Workers.

The one improvement would be if the author employed a greater sense of the sweep of history and a more dramatic narrative of the battles and strikes. The history is well laid out. It only needs a stirring voice that fits the heroic struggles of the miners.

Timothy Sheard is the editor of Hard Ball Press.