I have read about slavery and

I have read about slavery and it was really cruel. I am lucky I grew up in this generation where equality and independence is being practiced.

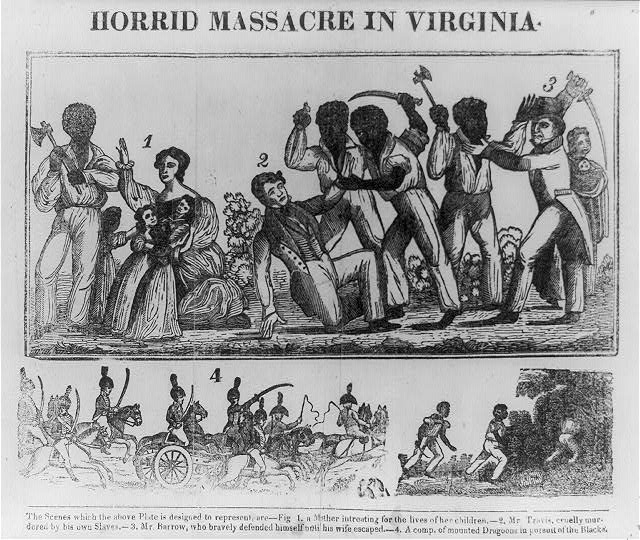

Missing from the film is the spark of slave rebellion and revolt that Solomon Northup portrayed so vividly in his book. Nat Turner led an 1831 revolt in Viriginia that killed 50-60 whites and struck terror into the hearts of the slave masters. Image: 19th century woodcut.

“12 Years a Slave,” the story of a free black man kidnapped by slave traders, has won an Oscar for Best Picture and a slew of other awards, including Best Writing for a screenplay adapted from another source—in this case the autobiography of Solomon Northup.

But in one important respect, the movie comes up short.

Missing from the film is the slave rebellion and revolt that Northup portrayed so vividly in his book. “12 Years a Slave” plays into that political current which sees exploited people only as victims, rather than people making history by fighting back.

“They are deceived who flatter themselves that the ignorant and debased slave has no conception of the magnitude of his wrongs,” Northup writes. “They are deceived who imagine that he arises from his knees, with back lacerated and bleeding, cherishing only a spirit of meekness and forgiveness.

“A day may come—it will come, if his prayer is heard—a terrible day of vengeance,” he continues, “when the master in his turn will cry in vain for mercy.”

Nat Turner led a bloody slave revolt in Virginia in 1831—10 years before Northup was sold into slavery. Turner rallied an estimated 70 or more slaves, and killed 50-60 whites.

Turner was later captured and hung, along with many others. But this rebellion struck terror into the hearts of the slave masters.

Herbert Aptheker documented 250 similar rebellions in his groundbreaking book, American Negro Slave Revolts. Northup writes:

Let them know the heart of the poor slave… and they will find that ninety-nine out of every hundred are intelligent enough to understand their situation, and to cherish in their bosoms the love of freedom.

Even before he was sold into slavery, Northup, living in Saratoga, New York, “frequently met with slaves, who had accompanied their masters from the South… Almost uniformly I found they cherished a secret desire for liberty…”

But where is this slave resistance in the movie? There is little to be seen.

The tone is set early on in a conversation between Northup and two other free men who have been kidnapped. “I say we fight,” says Robert, proposing a mutiny and seizure of the ship on which they are being transported. “The crew is fairly small,” says Northup. “If it were well planned, I believe they could be strong-armed.”

But Clemens responds, “Three can’t stand against a whole crew. The rest here are n**rs, born and bred slaves. N**rs ain’t got the stomach for a fight, not a damn one.” And, in the movie, that is the end of any talk of mutiny.

This is not the story Northup tells. He wrote that he and another kidnapped free man, Arthur, hatched a plot to seize the brig Orleans, on which they were being transported to New Orleans. They recruited another kidnapped man, Robert, who “entered into the conspiracy with a zealous spirit.” They developed a detailed plan to overpower the brig’s captain and crew.

They did not tell any of the other slaves about their plan, not knowing who to trust, but obviously counted on their acquiescence, if not support, once they seized control of the ship. The plan was only abandoned after Robert came down with smallpox and died, his body thrown overboard.

In the film, the only slave who fights back, once Northup gets to Louisiana, is Northup.

We see the slave Eliza weeping about being separated from her children. We see the slave Patsey beg Northup to kill her. Later Patsey speaks back to slave master Epps before being brutally whipped. And in one scene Northup stumbles onto the lynching of two slaves, although we never learn why they are being killed. That’s about it.

Early on in his autobiography, Northup meets a slave named Lethe in Richmond, Virginia. “Lethe… continually gave utterance to the language of hatred and revenge. Her husband had been sold… Pointing to the scars upon her face, the desperate creature wished that she might see the day when she could wipe them off in some man’s blood!”

Northup later relates a story where “some man’s blood” was shed. A certain slave, not far from the plantation on which Northup was enslaved, “was ordered to kneel and bare his back for the reception of the lash.

They were in the woods alone—beyond the reach of sight or hearing. The boy submitted until maddened at such injustice, and insane with pain, he sprang to his feet, and seizing an axe, literally chopped the overseer in pieces…

He made no attempt whatever at concealment, but hastening to his master, related the whole affair…

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

He was led to the scaffold, and while the rope was around his neck, maintained an undismayed and fearless bearing, and with his last words justified the act.”

Despite the near certainty of apprehension, “the woods and swamps are… continually filled with runaways,” Northup writes.

He even describes one incident where he is attacked by a group of escaped slaves trying to seize “a dressed pig in a bag swung over my shoulder.” Northup escapes, but acknowledges, “They had no evil design upon me, except to frighten me out of my pig… driven to this extremity by necessity.”

Northup also tells of a “concerted movement among a number of slaves” to escape to Mexico:

Lew Cheney, with whom I became acquainted… conceived the project of organizing a company sufficiently strong to fight their way against all opposition, to the neighboring territory of Mexico.

A remote spot, far within the depths of the swamp back of Hawkin’s plantation, was selected as the rallying point. Lew flitted from one plantation to another, in the dead of night, preaching a crusade to Mexico, and, like Peter the Hermit, creating a furor of excitement wherever he appeared.

At length, a large number of runaways were assembled; stolen mules, and corn gathered from the fields, and bacon filched from smokehouses, had been conveyed into the woods. The expedition was about to proceed, when their hiding place was discovered.

Unfortunately, Cheney then turned traitor:

Departing secretly from the encampment, he [Cheney] proclaimed among the planters the number collected in the swamp, and, instead of stating truly the object they had in view, asserted their intention was to emerge from their seclusion the first favorable opportunity, and murder every white person along the bayou.

Doubtless with Nat Turner’s revolt in mind, Cheney’s story “filled the whole country with terror.” The planters surrounded and surprised the runaway encampment. The prisoners, along with “many who were suspected, but entirely innocent,” were “without the shadow of process or form of trial, hurried to the scaffold.”

This revolt, although tragically aborted, became “a subject of general and unfailing interest in every slave-hut on the bayou.” Despite its tragic consequences, “such an idea as insurrection” persisted.

“More than once,” Northup relates, “I have joined in serious consultation, when the subject has been discussed, and there have been times when a word from me would have placed hundreds of my fellow-bondsmen in an attitude of defiance. Without arms or ammunition, or even with them, I saw such a step would result in certain defeat, disaster and death, and always raised my voice against it…

“It is a mistaken opinion that prevails in some quarters, that the slave does not understand the term—does not comprehend the idea of freedom…”

Despite Northup’s counsel against insurrection, he fought back when he had no choice. The movie graphically portrays a fight with a white carpenter, John Tibeats. As graphic as it is, the beating Northup gave Tibeats was even more brutal than shown in the film:

I placed my boot upon his neck. He was completely in my power. My blood was up. It seemed to course through my veins like fire… I snatched the whip from his hand… I cannot tell how many times I struck him. Blow after blow fell fast and heavy upon his wriggling form.

At length he screamed—cried murder—and at last the blasphemous tyrant called on God for mercy. But he who had never shown mercy did not receive it. The stiff stock of the whip warped round his cringing body until my right arm ached.

In the book, but not in the movie, Northup has a second fight with Tibeats, in which he once again overpowers the carpenter. This time Northup flees, eludes a pursuing party of hounds and takes refuge in the swamp. Eventually, as after the first fight, Northup is saved from deadly retaliation by the intervention of his first master, William Ford, avoiding that “certain defeat.”

I don’t know how the movie “12 Years a Slave” came to downplay revolt, despite its prominent place in Northup’s autobiography. But there is a current among some who call themselves progressive to see exploited people as mere victims, meekly waiting for deliverance from some savior.

It appeases the conscience of some liberals, but it is not a true story. People fight back against their oppressors. It's part of human nature.

Sometimes we fight back smart, and sometimes we just fight back. Sometimes we are organized, and sometimes we are disorganized. But history is the story of rebellion after rebellion.

Marc Norton is a member of UNITE HERE Local 2 and the Industrial Workers of the World. His website is www.MarcNorton.us. A longer version of this piece originally appeared in the San Francisco BayView.

I have read about slavery and it was really cruel. I am lucky I grew up in this generation where equality and independence is being practiced.

What is the reasoning behind this article?