Contracted Hospital Workers Win Job Security

For the first time in 15 years, 4,000 subcontracted hospital housekeepers and dietary workers in British Columbia have job security. Photo: Nimfa Torrente

For the first time in 15 years, 4,000 subcontracted hospital housekeepers and dietary workers in British Columbia have job security. They won that peace of mind by pulling off a series of escalating actions on the job.

Between 2002 and 2005 the provincial government, headed by the Liberal Party, fired 10,000 hospital support service workers—mostly women and people of color—and subcontracted their jobs to multinational corporations including Aramark, Compass, Sodexo, and Acciona.

In the years that followed, the workers who were hired back—less than half of those who'd lost their jobs—reorganized with the Hospital Employees’ Union (HEU) and bargained hard to regain what they’d lost. But without job security to protect against another change of contractor, all gains were precarious.

In 2015, for example, Aramark’s largest contract was flipped to Compass. More than 800 members were laid off and forced to reapply.

These workers, many of whom had worked for Aramark for more than 10 years, became probationary employees with no union, no collective agreement, no seniority, and no security. And to top it off, Compass created a new “light-duty” position that paid almost $2 Canadian less.

TURN UP THE HEAT

Hospital support service workers won job security by starting small and turning up the heat ...

- Black Friday T-shirt & sticker day

- March on the FHA Board Meeting

- Worksite leafleting

- March on the VCHA Board Meeting

- Overtime ban

- Set a strike deadline

- Job action pledges

- Strike votes

- Rally at St. Paul’s Hospital

- Job security petition delivery

- Hospital leafleting

- Orange shoelaces

- Report-out meetings

- Job security petition

Learn to plan an escalating campaign with Secrets of a Successful Organizer. Buy the book and download free handouts like the Action Thermometer at labornotes.org/secrets

YOU START WITH A PETITION

In response, members decided to act during the 2016 round of coordinated bargaining. Eleven bargaining units of contracted workers all had a common expiration date, September 30. The 60 elected bargaining team members made common proposals across all the tables and met a dozen times to coordinate field actions.

The first was a petition calling for job security—a tool for bargaining leaders to start one-on-one conversations with co-workers and track those discussions. The petition was also the first test of the union’s reach: Were there enough bargainers in the 75 different worksites to reach a supermajority of the membership? How long would it take?

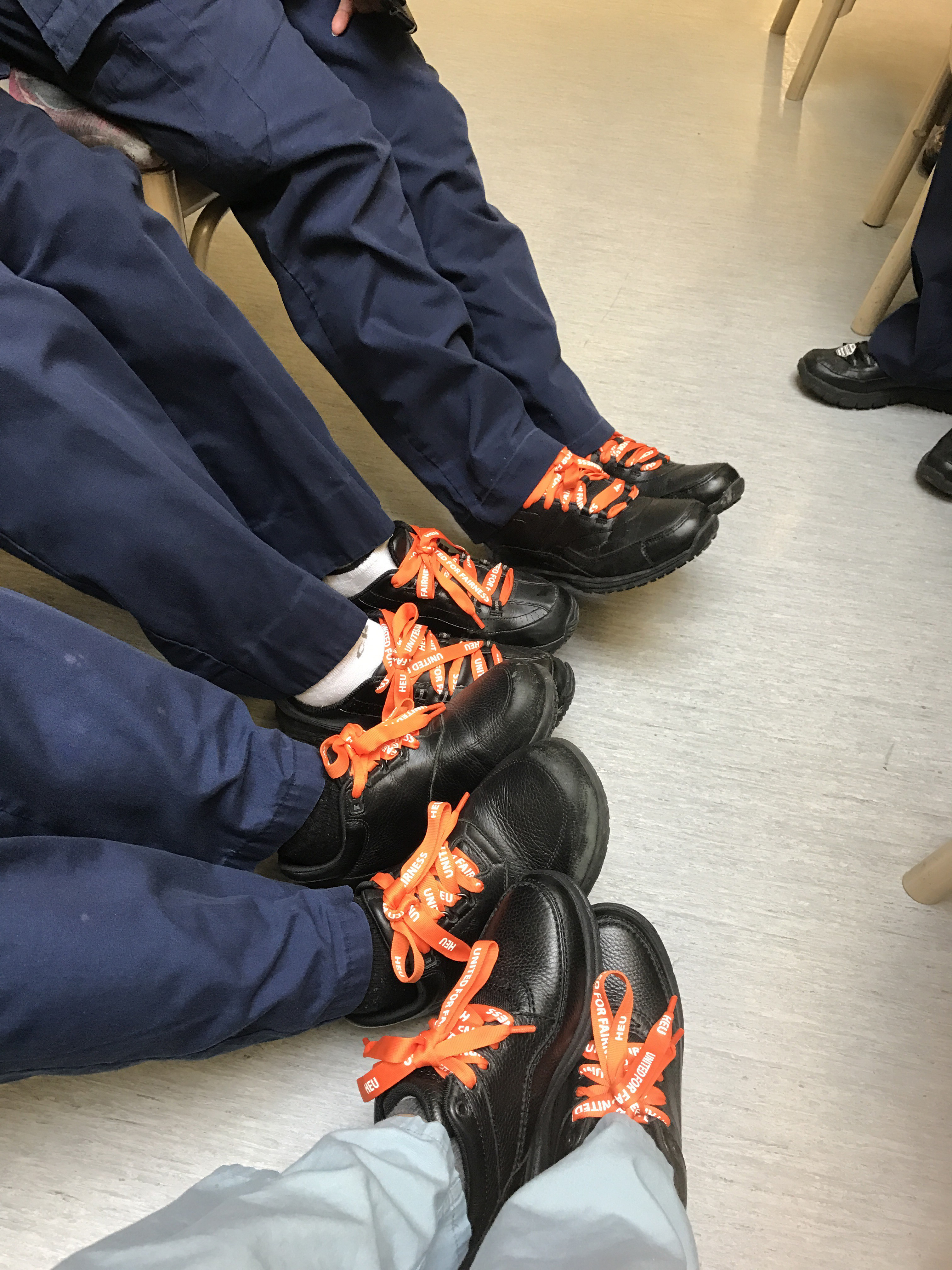

During this time, bargainers held a series of well-attended worksite meetings to report on bargaining, another opportunity to connect with members. They were also where members organized their next action: on March 13 they donned orange “United for Fairness” shoelaces in a circumventing of company uniform policies and a show of solidarity.

Once they had reached a majority of members on the petition, in May 2017, bargaining leaders printed up a huge poster showing the names and worksites of all the signers, and organized their co-workers to march on company managers at each hospital to deliver the petitions.

Five hundred members participated in these marches, at the 25 largest hospital worksites. For many, it was their first time participating in a collective action on the job.

“I spent the week before talking to my co-workers one on one,” said Clarissa Hicap, a housekeeper at Vancouver General Hospital and a bargainer with Compass.

Still, she was nervous on the march to the Compass office. “I beat the hand drum I’d brought from home with every step we took,” she recalled. “When I looked behind me, I saw at least 70 of my co-workers had joined in the march!”

Workers say these marches changed the dynamics on the job. “Our managers and supervisors treated us with no respect,” Hicap said. “But after we marched to deliver the petition, I could tell something changed.”

STRIKE VOTES

Employers didn’t yet feel enough pressure at the bargaining table, so leaders began preparing for a strike vote.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Hospital executives denied them meeting rooms inside, so in June 2017 members took their votes to the street, pitching tents and tables on the sidewalks and green spaces in front of the hospitals. Ninety-six percent of members voting said yes to a strike.

Workplace leaders continued to organize through the summer, gathering strike pledges from their co-workers. The pledges were once again a tool for one-on-one conversations, where leaders dispelled fear and answered questions about how escalating job action might proceed.

These conversations allowed leaders to track which areas of each worksite had enough support for successful action, so they could see where they needed further conversations.

REFUSING OVERTIME

By fall, employers were still refusing to bargain seriously; Compass refused even to set bargaining dates. It was time to step it up.

Leaders decided the first sector-wide job action would be a refusal to work overtime on a certain weekend. The overtime ban was a huge success, involving 2,800+ members at 32 worksites. To pick up the slack managers found themselves washing dishes, serving food on the tray line, and taking out the garbage.

By the end of the weekend, “we could see how relieved managers were to get back to their own jobs,” said Gwenda Alexander, a Burnaby Hospital housekeeper and Aramark bargaining team member.

The action gave workers a further sense of their collective strength. “Members felt they finally had the power to say no,” Alexander said. “The overtime ban exposed the problems that come from the employer’s chronic understaffing.”

CRASHING THE BOARD

Now tensions were high. Members prepared for picket lines. And true to form, rather than negotiate a deal, employers focused their energy on trying to stop the job action, filing multiple legal challenges at the provincial labor board.

Compass, especially, still needed a wake-up call. In October, 100 HEU members crashed the Vancouver Coastal Health authority’s board meeting to protest Compass’s refusal to bargain.

As Compass’s “employer,” Vancouver Coastal Health, which serves a quarter of the province's population, had the power to press Compass back to the table. By the end of the following week bargaining was back on—and in an added victory, Compass finally agreed to HEU's demand for a single bargaining table for all five units.

Members continued to press Compass and Sodexo with hospital leafleting, a march on the Fraser Health Authority board meeting, and a T-shirt day when almost 2,000 members ditched their corporate uniforms for “United for Fairness” t-shirts. Compass workers leafleted patients, families, and co-workers in their cafeterias, advising them to “bring their lunch,” as a picket line was imminent and the cafeterias would be shut down.

By the end of October tentative agreements were reached without a picket line with Sodexo and Compass, the last two employers to settle. All employers improved benefits and contract language, and most wage increases were retroactive to fall 2016.

The major victory, though, was job security. In an agreement bargained between HEU, the Ministry of Health, and the regional health authorities, now when commercial contracts are re-tendered, contracted support service employees in HEU will keep their jobs, their union, and their collective agreement.

Laurel Albina works for the Hospital Employees' Union in Vancouver, British Columbia.