50 Years after Memphis: Black Jobs Crisis Continues

What has happened to Black workers in the 50 years since the Memphis strike, after the upsurge of Black worker activism, the assault on labor by economic elites, the rise of income inequality, and the surge of right-wing authoritarianism? Photo: ATU Local 732

On February 1, 1968, Echol Cole and Robert Walker left their homes for their jobs as Memphis sanitation workers. They never returned alive. They were crushed by a malfunctioning garbage truck. Their deaths sparked a strike by their 1,300 union brothers.

The strike was victorious only after months of protests, strong community support, the intervention of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King.

While history remembers the strike as the last campaign of Dr. King, a more accurate reading presents it as one of several episodes of Black worker activism that occurred in the late 1960s and the 1970s.

Hospital workers struck in Baltimore and Charleston, South Carolina. Black workers formed caucuses in many unions, notably the Steelworkers and Auto Workers. Black labor leaders started the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists in response to the conservatism of the AFL-CIO leadership. And Black workers were active in strike waves and organizing drives in the public and private sectors.

What has happened to Black workers in the 50 years since the Memphis strike, after the upsurge of Black worker activism, the assault on labor by economic elites, the rise of income inequality, and the surge of right-wing authoritarianism?

STARK GAP

Some job conditions for Black workers have improved, but not nearly enough to catch up with white workers—and that is partly due to the fact that conditions for all workers have been under attack.

Part of the context for racial inequality since the mid-1970s is captured by the stark gap between the growth of labor productivity and the growth of wages (see the graph). Since 1979, labor productivity has risen by 64.2 percent but wages have risen only 10.1 percent.

This gap reflects the aggressive attack by economic elites on all workers. It means that while Black workers today earn 82 cents for every dollar earned by white workers—an improvement since 1968—neither group has fared well: wages for Blacks rose by 0.6 percent per year; wages for whites by 0.2 percent per year.

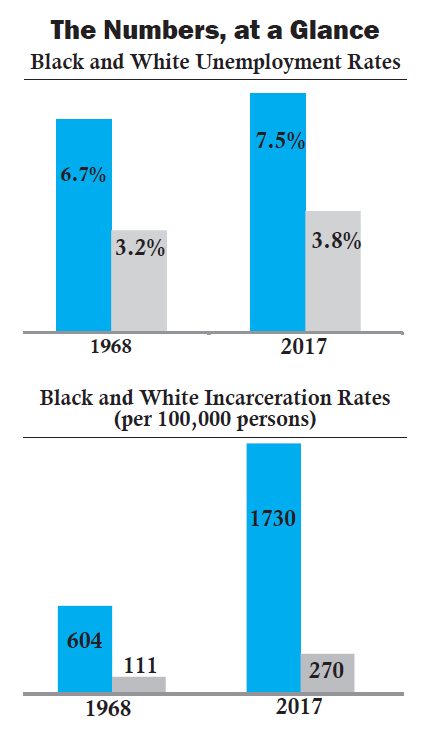

For 50 years, the Black unemployment rate has remained twice that of whites (see graph). The incarceration rate for Blacks has risen more rapidly than the rate for whites: in 1968, Blacks were 5.4 times more likely to be incarcerated compared to whites; by 2016, Blacks were 6.4 times more likely to be incarcerated.

A month before he died, Martin Luther King said of Black workers, “The problem is not only unemployment, it is under or sub-employment… people who work full-time jobs for part-time wages.” This is still the case today.

If we use as our definition of “low-wage” two-thirds of the median wage of a full-time worker (at the national level, this makes “low-wage” $12.60 an hour), in 2010-2012, 38.1 percent of black workers earned low wages, compared to 25.9 percent of white workers.

ACTIVISM GENERATED

Just as Black Power activism in the 1970s spawned a wave of protests by Black workers, today’s Black Lives Matter movement has generated new Black worker activism.

After the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, the AFL-CIO established a Racial Justice Commission and held hearings around the country on racism within unions. The Service Employees union did likewise and committed itself to becoming a racial justice organization.

AFSCME's “I Am 2018” campaign honors the heroes of Memphis 1968 and commits the union to continuing their fight. The Food and Commercial Workers have supported efforts to restore rights for the formerly incarcerated.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

UNITE HERE has renewed efforts to increase Black employment within the hotel industry. Public sector unions have held conferences on expanding the goals of their collective bargaining, under the umbrella of “Bargaining for the Racial Good.”

Outside the formal labor movement, Fight for $15 has aggressively linked its efforts to raise the wage in the fast food industry with efforts to fight police brutality. The Restaurant Opportunities Center has challenged racial segregation in the restaurant industry, demanding more front-of-the-house jobs for Black and Latino workers.

OUR Walmart has done education so its members are more aware of racism felt by non-white Walmart workers. Worker centers in Chicago have fought anti-Black discrimination by temporary staffing agencies.

Affiliates of the National Black Worker Center Project have led a variety of campaigns: to get Black workers into the L.A. construction industry; to get the government of Alameda County in the Bay Area to directly hire the formerly incarcerated; to lower traffic fines faced by New Orleans residents.

It is all well and good to discuss broad policy solutions to racial and economic injustice, such as a “universal basic income,” guaranteed job programs, and a new Urban Marshall Plan. But such discussion must occur within the context of sustained organizing and power-building on the ground.

Steven Pitts is Associate Chair of the Labor Center at UC Berkeley.

Inspired by Memphis 1968, Atlanta Transit Workers Strike

Chanting “the workers united will never be divided,” Atlanta paratransit operators showed themselves some love with a one-day strike on Valentine’s Day.

Inspired by the 50th anniversary of the 1968 Memphis sanitation workers strike where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his life, workers carried signs saying, “I Am a Woman” and “I Am a Man.”

About 75 workers picketed MV Transportation, the largest private provider of paratransit services in the U.S., and a subcontractor, Atlanta Transportation Services. Despite protests by Transit (ATU) Local 732 and the disability community, the Transit Authority (MARTA) board had voted in 2015 to privatize its paratransit service.

Under MV and its subcontractor, MARTA Mobility workers have seen their wages and benefits cut.

Executive board member Stanley Smalls said drivers were concerned for their passengers. The paratransit vehicles “blow so many fumes inside the buses where operators are driving and getting dizzy,” Smalls said.

Though the union won its arbitration case against MARTA's outsourcing, MARTA got a judge to rule in management’s favor. The union is appealing while in contract talks with MV.

The strike was the first official one at MARTA since the transit authority was formed in 1971.

Paul McLennan is a retired bus mechanic and member of ATU Local 732.