Ohio Teachers Win Back Regular Raises

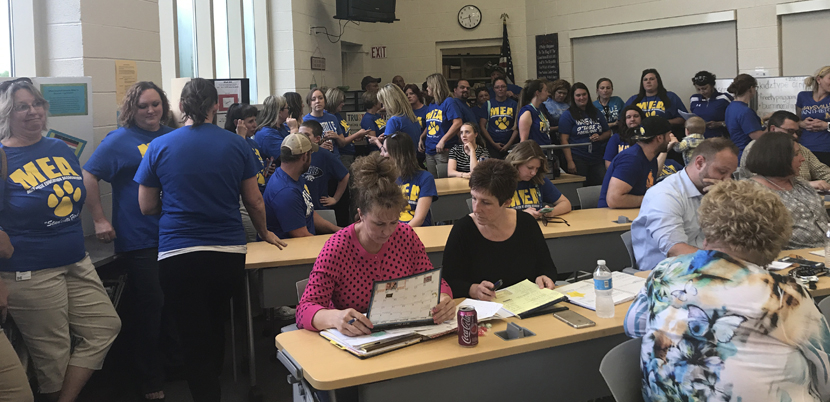

Maysville teachers packed a school board meeting as part of their contract campaign. Photo: Maysville Education Association

In 2014, members of the Maysville Education Association voted to accept a deal that would end our pay freeze, which dated back to 2011, in exchange for replacing our traditional pay scale with a new merit-pay system.

Local union leaders were warned by Ohio Education Association staff that a return to the step-and-ladder system of regular raises might be impossible—or require a strike. But this year, as the money for sweeteners and incentives dried up, a group of members committed to winning back our old pay scale.

This was no small challenge for a local with 140 members in rural southeastern Ohio. Nobody could remember the last time more than 25 or 30 people came to a meeting.

Previous negotiations had been fairly informal, and little had been done to involve the members. Traditionally, the superintendent encouraged our union president to strike a contract deal behind closed doors. When I became president in 2015, I promised to promote greater transparency and member involvement.

Making our job more difficult, about a quarter of our members were doing better with merit pay than they would have under the traditional system. Some wouldn’t get a raise if we returned to the old salary schedule, since they had passed the top rung. But the other 75 percent of members had seen their pay stagnate for years. We had to convince those who were benefiting from the new system to support our efforts—and that when management pits us against one another, it’s bad for the union as a whole.

We also had to unite members who work in different buildings and on different schedules. An all-call for negotiating committee members produced 10 volunteers from different work areas and buildings who agreed to meet weekly, beginning in January.

PREPARING OUR CASE

We elected to open every article of the contract—a move that was long overdue. Our contract had not been looked at in detail for decades. For instance, one clause suggested that the superintendent had the right to determine whether a teacher who had given birth was emotionally fit to return to work. In other areas, such as family medical leave, our contract language violated federal law.

Committee members were assigned to review specific articles. We examined other locals’ contracts and our own members’ survey responses, and made recommendations based on our research. After discussion, we agreed on our bargaining priorities.

Another critical step was to analyze the district’s spending and financials. Our statewide union filed a Freedom of Information Act request on our behalf for all district salaries and compensation, revealing wide disparities in pay.

For instance, we found one teacher who would have to work 21 years under the alternative compensation plan to reach a salary of $51,500—the amount executive secretaries in the administration center are paid right away. This person agreed to serve as a poster child.

It wasn’t enough to just say, “This is good for young teachers.” We made sure we got permission to use people’s names, both at the bargaining table and with other members, so that we would have concrete examples.

Our research also revealed that the district was top-heavy in administrative salaries—employing 17 administrators, who cost taxpayers $1.5 million, compared to 12 administrators in a similar-sized neighboring district. The union’s analysis of the district’s financials also revealed that the year it implemented merit pay, the district had saved $700,000 on its staff payroll—money taken right out of teachers’ pockets. And while the district was pleading poverty, its books showed $1.3 million in revenue over expenses.

MEMBERS CHOOSE

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Highlighting these financial disparities got members engaged. But we needed a strategy to hold their interest through the bargaining process.

Committee members worked tirelessly to collect personal emails and cell phone numbers from all members. We insisted that people use their non-school email addresses, so that administrators couldn’t read our messages. Sometimes we even had to help a member set up a personal email. The bargaining team sent out regular emails and reminder texts to inform members of progress and ask for support at crucial times.

While negotiations were ongoing, we asked members to wear union shirts, participate in solidarity walk-ins, and show unity by dressing in assigned colors such as red or grey. We held after-school mixers to encourage camaraderie among teachers from different grade levels and buildings. This support was crucial to keeping the team motivated as negotiations lumbered on past the close of the school year.

We also kept members informed of the substance of negotiations and involved in key decisions. After the first two days of bargaining, in which the district insisted on maintaining the merit pay system, we told their negotiating team that we needed to get member input before we could proceed. On May 9, we held a meeting attended by two-thirds of our members—absolutely unheard of in our district. At the meeting, we presented members with a PowerPoint outlining three choices:

- Continue to fight for the traditional step system

- Acquiesce to the alternative compensation scheme, but try to get a better deal

- Try to work with the administration to come up with a combination of the two

After the presentation we handed out index cards and asked members to vote. Ninety-one percent chose to keep fighting to win back the step system.

WHATEVER IT TAKES

A turning point for us was getting 90 members to a school board meeting—so many that the board hired a sheriff to watch over us.

Board members were also aware that 122 of 140 union members had signed a petition agreeing to do “whatever it takes” to regain a traditional pay schedule. Once they saw that, they knew they had to take us seriously.

Bargaining concluded on June 2 with a return to the traditional pay scale—making us the first local in Ohio to win back our salary schedule after giving it up. Additional gains included:

- a grandfather clause, insuring no member would be expected to take a pay cut

- financial penalties if the district exceeded class-size targets—the affected teacher would get an extra $200 per student additional release days for our special education teachers

The lone concession was an agreement to add 15 minutes to our work day, bringing us into alignment with other local districts. The contract was ratified with a 91 percent yes vote.

Preparation, communication, and unity were the keys to our success. We began early, asked members for input, created an expectation that members would participate in the contract campaign, and refused to back down at the table. Countless hours of research helped too. Going forward, our challenge is to maintain our new solidarity and continue to develop relationships among members.

Myra Warne is the president of the Maysville Education Association and an English teacher at Maysville High School.