Campus Workers Smell a Rat

Following their first-ever strike last fall, Pennsylvania faculty members continued to organize. Photo: APSCUF

When students and faculty at Pennsylvania’s Kutztown University returned to campus in January after winter break, Lytle Hall became the building to avoid. It stunk. The moment you entered the main doors of the building, you were greeted by the overwhelming stench of a rotting animal.

As it happens, Lytle Hall was the building where several union leaders had our offices, including our local president, membership chair, adjunct faculty chair, and me, chair of the mobilization committee. Faculty at Kutztown are members of the Association of Pennsylvania State College and University Faculties (APSCUF). For three days last fall, the 5,500 faculty members and coaches in 14 state-owned universities walked out on our first-ever strike.

So when we came back for the spring semester, we were still in organizing mode. During our strike mobilization, Membership Chair Mike Gambone had established a system of building captains. Now he aimed to keep the building captain system going with actions to address the health, safety, and working conditions in our academic buildings. The Lytle stench fit right into his plan.

Lytle Hall had a long history of health problems, including mold, poor air quality, and corroding systems for heating, ventilation, and air conditioning—not to mention cramped office space, unreliable Wi-Fi, and hot classrooms. Gambone had already been organizing faculty members to push the administration to address the long-standing health issues. Our next organizing issue was obvious: the Lytle stench.

‘NOTHING WE CAN DO’

Gambone and other members started by talking to faculty and department secretaries (AFSCME members) about the problem. He showed people how to file work orders to get the stench addressed. It should have been a pretty easy fix, since members had identified a specific heating/cooling unit in the entryway as the likely source of the smell.

Management refused to send facilities workers out to fix the problem. As part of a decade of austerity, the university has gutted its facilities staff—and Lytle Hall has been low on management’s priority list for years. The fact that several leaders of the recent strike had their offices there in the building probably didn't put our problems at the top of the administration's to-do list, either.

Next Gambone emailed all the Lytle Hall faculty members, reminding them of the lesson from their recent strike: that they had the power to solve problems with collective action. He invited every member to file a work order, complain to administrators, attend a public meeting, or contact Pennsylvania’s Department of Labor and Industry.

But despite multiple emails to deans, the provost, and facilities managers, the week ended with no solution. A department secretary received an email back from the facilities office. “I just rejected your request about the smell in the stairwell,” the email said. “We called over a custodian with a spray to help eliminate the smell. At this point, there is not much we can do if it is dead in the wall, which we think it is.”

RATE THE SMELL

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

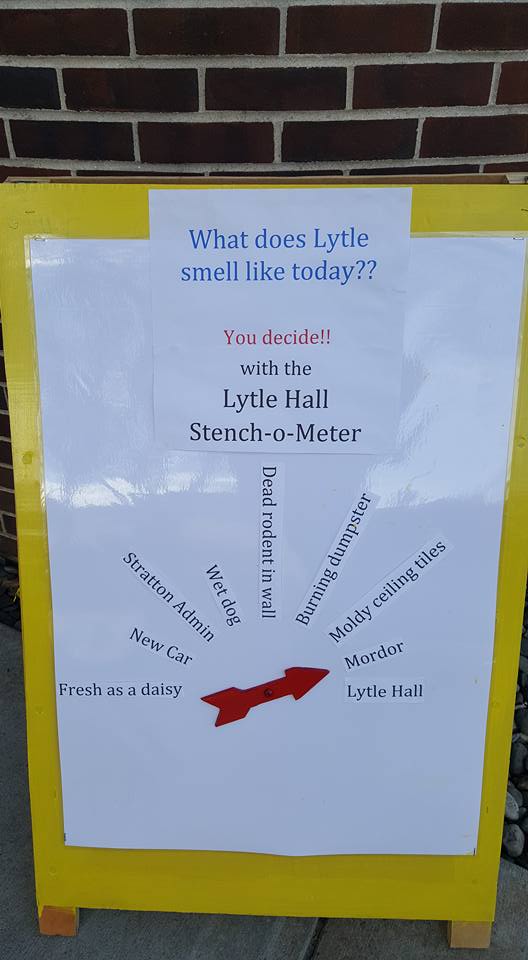

The following Monday morning, Gambone unveiled his weekend project: the Lytle Stench-O-Meter. Faculty, staff, and students on their way in through the building’s main doors were greeted with a bright yellow sandwich board asking: “What does Lytle smell like today? You decide!”

The board had a giant dial. Anyone could move the arrow to choose a smell, ranging from “fresh as a daisy” or “new car” to “burning dumpster,” “Mordor,” or, worst of all, “Lytle Hall.”

Faculty members and students stepped right up to turn the dial and post their photos to social media. We started tagging local reporters on the posts. Soon news media were contacting the university’s public relations office.

The university president called our union president, pissed off about the publicity the Stench-O-Meter was getting. That’s right—he was pissed about the publicity, not that managers were refusing to fix the problem. But by the end of the day, facilities workers were taking apart the heating/cooling unit in the entryway, removing a nest full of rotting rodent remains.

WIN AFTER WIN

It’s safe to say that without the publicity from the Stench-O-Meter, the faculty, staff, and students would just have had to suck it up and learn to love the smell of rotting flesh. Instead, our collective action solved the problem—and encouraged members to keep fighting on the other health issues at Lytle Hall.

Our building captains kept up the pressure about mold, air quality, and corroding ventilation units. After we filed complaints with the Bureau of Labor and Industry, state inspectors came and confirmed our concerns. The administrators who had insisted there was no problem were left with egg on their faces.

Recently faculty and staff had to pack up all our belongings and move out of our offices for the summer. That’s because our building is finally being renovated to remediate the mold problem, remove asbestos, and replace the outdated and malfunctioning units. None of that would have happened if we hadn’t stood together to demand a safe, healthy workplace.

Kevin Mahoney is a professor of composition and chair of the mobilization committee at APSCUF-Kutztown University.