Taking a Bite Out Of Overtime Abuse

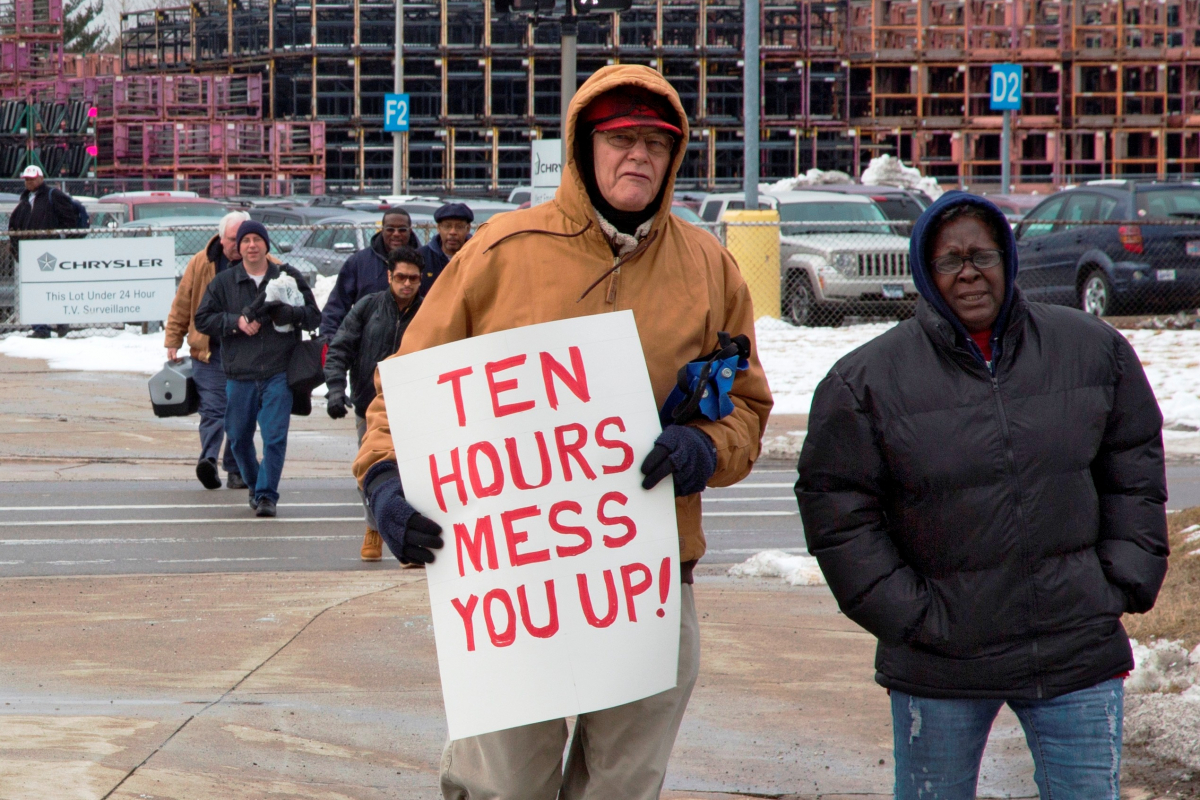

UAW members picketed a Chrysler plant where a horrible new schedule was launched last year. Photo: Jim West/jimwestphoto.com.

“When you get up, the kids are sleeping. When you get home, the kids are sleeping.”

That’s how Rich Pawlikowski, a UPS package car driver in Queens, New York, described his lengthening workday. “Only six to eight years ago, the summer months were light. [Now] they send us out with 10, 11, 12 hours of work,” he said.

“It’s not healthy. You’ve got to get some rest. When the end of week comes, you see all the accidents and injuries.”

UPS, with its growing package business, isn’t refusing to hire because it’s hurting. On the contrary, business is booming. Like other chronic overtime abusers, such as lucrative television production companies and Verizon with its fat franchise agreements, UPS does it because it can.

Contract provisions and laws can help. But those only get enforced if workers get organized and do it themselves.

It takes vigilance, member involvement, and in some cases a collective “Hell no!”

An overtime boycott by hospital nurses, for instance, got management’s attention fast (see “Pushed to the Wall, Nurses Refuse Overtime”). They were helped by a law against mandatory overtime, but only saw motion after emergency room staff refused any assignments.

CHRISTMAS DEBACLE

UPS Teamsters have long had contract provisions to curb overtime abuse. But workers in New York found direct action was required to get the full benefit.

The contract allows drivers to file a grievance if they work more than nine-and-a-half hours for three days in a given week. The penalty is triple-time pay for hours worked over 9.5—but what the drivers really want is a load adjustment, so they can get home before 10 p.m.

Pawlikowski said he kept grieving it, but management wouldn’t adjust his workload, preferring to pay the penalty.

During the last two Christmas seasons, Pawlikowski said, they were so understaffed that he and his co-workers were unable to get through the work. The company got nervous and even set up a task force to study the problem.

Then in February, 250 Queens drivers, members of Teamsters Local 804, were suspended after a short work stoppage. Though the immediate cause was to protest the firing of one of their members, that came on the heels of an accumulation of other contract violations.

The company started firing them in waves, but a vigorous union campaign and community pressure forced the company to rehire everyone by April.

After that flexing of union muscle, managers started adjusting workloads in earnest. The company has even started hiring.

“Drivers are ecstatic,” Pawlikowski said.

The system is elaborate. Workers have to go to a manager to get on the “9.5 list.” Previously, managers simply posted the list, but so many people signed up, they took it down. Now managers try to gatekeep.

Dodging Overtime Pay

Among infamous dodges of overtime law is classifying your workers as supervisors and paying them a salary that doesn’t change no matter how many hours they put in.

Employers stretch the definition of “supervisor” beyond recognition. Rules instituted in 2004 provided for “concurrent duties,” meaning workers can be alleged to be supervisors while they work line jobs, said Ross Eisenbrey of the Economic Policy Institute.

In a recent case Dunkin’ Donuts counter workers were called supervisors, even though they only worked the register. They were working up to 65 hours a week without any overtime pay, he said. Catherine Ruckelshaus, with the National Employment Law Project, cited similar egregious overtime violations at Pep Boys and Auto Zone.

OBAMA MOVES

Then there’s the exemption from overtime pay for well-paid “executive, administrative and professional” workers. A salary cap instituted in the 1970s to determine eligibility is now laughably low.

Make more than $455 a week and you could be exempt. The equivalent figure in 1975 was double that. (In New York and California, state caps are higher).

The threshold is so absurd that President Obama in March ordered the Labor Department to come up with new rules. They haven’t been announced yet, but will likely raise the limit to somewhere between $550 and $970.

That would be a solid gain, said Ruckelshaus, because a “bright line” test like a salary figure is easy for workers to understand and harder for employers to skirt.

“They always threaten, some people get intimidated. But there’s nothing they can do to you except look at you funny,” said Pawlikowski. The union provides advice and forms.

Once you’re on the list, you can tell them how much overtime you want. The limits don’t apply during peak—from Thanksgiving to New Year’s—but the improvement is noticeable.

“That’s the beauty of 9.5,” said Pawlikowski. “You get everybody on the list, it creates jobs, you get to see your family, everybody’s happy.”

REALITY BITES

Writer-producers in the highly profitable “nonfiction” section of television production, known to most of us as reality TV, are deemed “exempt” and not eligible for overtime pay—even when they work grueling 80- to 100-hour weeks. (See box at right.)

These workers create the ideas in the shows, develop scenarios, write interview questions and even dialog, prep characters, set up shoots, film, tear down, and move to the next location.

A 30-year veteran of the industry said union jobs she’s worked paid $2,500-$3,500 a week—but these non-union jobs are paying $1,000. With the long weeks, it works out to $10-12 an hour.

On a union job, she said, “You work, put in a few extra hours…but I’m not working seven days a week for a month without a day off. You can say no.”

“Production companies are trying to deliver TV shows at cheaper and cheaper prices,” said Justin Molito, an organizer with the Writers Guild (WGAE). The shows are increasingly being made on a shorter timeline and with longer hours, he said.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

A union survey in New York found that 84 percent of writer-producers worked more than 40 hours a week, every week, and 85 percent never received overtime pay. The union estimated the wage theft at $40 million a year.

That’s starting to change now that the Guild is organizing the workforce. About one-third have already voted the union in, said Molito. That and the prospect of being sued for wage theft have made some employers curb their worst abuses.

Still, workers are going before New York’s city council to expose labor violations in nonfiction TV—which is, not coincidentally, the most profitable segment of TV production.

NOT GETTING BETTER

While overtime use goes up when the economy gets better, usually abuse goes down, said Catherine Ruckelshaus of the National Employment Law Project. That’s because workers are more able to stand up for themselves.

But not in this recovery. “In the low-wage sector, it’s still a buyer’s market for the employer,” she said.

Overtime violations are rampant. These include clocking people out before they’ve finished working, paying straight time when overtime is required, misclassifying workers—like those in nonfiction TV—as exempt professionals, and claiming workers are supervisors when they aren’t.

Allegedly “independent” contractors are even found in unionized auto plants, where fly-by-night hiring agencies have workers on 10-hour days, seven days a week, with no overtime protections and at rock-bottom pay.

After this article ran in print, a truck driver called us who works 12-hour shifts, six or seven days a week, transporting parts for a Ford assembly plant in Chicago. But “we don’t get overtime or anything,” he said.

That’s because the company that pays him, CWS, has been getting away with the “independent contractor” ruse for years—though it’s clear he and his co-workers should legally be employees. The boss sets his hours, he punches a time clock, and he certainly doesn’t own the truck he drives. “Half the time we don’t even get to have lunch,” he said.

It’s a common setup. The driver said CWS has accounts with GM and Chrysler too.

NOT ENOUGH PENALTY

Overtime premium pay is part of the Depression-era Fair Labor Standards Act. It was intended to cause employers to hire more workers, by making it more costly to push existing workforces into longer and longer hours.

But the deterrent doesn’t work unless there’s enforcement to keep employers from ducking the premium, said Ruckelshaus.

Even when employers are forced into paying the premium, time-and-a-half may not be enough to have the intended effect.

Ironically, good union contracts can make paying time-and-a-half cheaper than hiring additional workers. A 1990s study by Labor Notes found that in the auto industry, only double-time pay provided enough of a goad to get factories to hire more people. This was because “adding another Social Security number” carried its own costs in training, health insurance, workers compensation, and pension coverage.

Workers at Verizon can’t remember the last time the company was hiring, but it’s not for lack of work. Verizon promised in a 2008 franchise agreement that it would finish installing its fiber optic network (FiOS) in New York City by June 30, 2014. The city can impose penalties for lateness.

Don’t Let Overtime Lists Get Hinky

Overtime can get contentious among union members, but it’s a sleeper issue until there’s not enough overtime for those who want it.

At Verizon, overtime is a close second to discipline as the subject of grievances, Communications Workers say. In departments where the steward doesn’t keep on top of management to maintain correct records, disputes can flare up.

The solution is vigilance, even when there’s plenty of work, before it becomes an issue. It also helps if the list is public and tons of people are looking.

Then the complaints go away, said UAW member Alex Wassell. For stewards at his plant, “‘Thou shall keep the hours straight’ is like the eleventh commandment.”

Instead of hiring more staff locally, the company has been pulling workers away from their homes in other parts of the Northeast for three-week shifts. Local employees, members of the Communications Workers (CWA), are working three out of four Saturdays. Even those who volunteered for the FiOS build-out, hoping for lots of overtime to pay debts or big bills, are starting to balk.

The company announced in June that it will miss the deadline. Instead of examining its hiring practices, it blamed hurricanes, uncooperative landlords, and even the 2011 strike by CWA and the Electricians (IBEW), even though in 2013 it claimed to be ahead of schedule.

‘AWFUL WORK SCHEDULE’

A scheme to evade Saturday overtime pay hit autoworkers last year at two Detroit-area Chrysler plants.

The Autoworkers (UAW) contract provides for overtime pay for working on Saturdays. But the company created a 10-hour shift system, the “Alternative Work Schedule,” with two-thirds of the production workforce scheduled every Saturday—at straight time. The idea is, it doesn’t count as a weekend if it’s part of your regular schedule.

Half those workers must switch back and forth between day and evening shifts each week. The system also evades break and lunch times.

Even the best shift, Monday through Thursday, 5:30 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., is grueling, said Alex Wassell, a welder repair technician at the Warren Stamping Plant.

“It’s a long day [on that shift], too,” he said. “Even three days in a row off, you’re still tired on the 10-hour-a-day schedule.”

To the dismay of rank and filers, the union allowed the unpopular new schedule to stand. UAW’s vice president even tried to sell it to indignant members at a raucous meeting with Warren Stamping workers. Local 869 members at the plant organized against it—petitioning, wearing stickers, mass-texting the company and the union, even picketing the plant.

After the picket, Wassell was fired for supposedly disparaging the company. He got reinstated and won a long fight to clear his record.

For now, the bad schedule prevails at Warren Stamping. But “Sterling Stamping is still on the traditional schedule,” Wassell said, and “that could have been because of the ruckus we made. Management and union felt they’d stay with what they had.”

Members of the local are making abolishing the “awful work schedule” a high priority in 2015 negotiations. If they’re still on it after that, Wassell said, “people will be beyond themselves.”

Alexandra Bradbury contributed to this article.

You must log in or register to post a comment.