Mid-Term Concessions: Saving Your Shirt

Every day it’s front page news. Another company closes, big unions take concessions, municipal workers go on furlough. The boss puts your members through a one-hour PowerPoint on competition in China and India.

The day arrives when he asks for concessions. How do bargainers respond?

THE GROUND RULES

The first question to ask is: what happens if the parties cannot agree? In normal bargaining an impasse allows management to impose an agreement unilaterally. Impasses can be broken by strikes, corporate campaigns, boycotts, or on-the-job actions that cause the company to change its mind and keep talking.

In midterm bargaining, though, with a contract in place, a no-strike, no-lockout clause is usually in effect. Slowdowns and other actions are difficult. Does the company think that it can claim impasse and impose its terms? If so, don’t re-open.

Do Concessions Work?

When employers catch a break on labor costs, the bottom line looks better. But do concessions meet any of labor’s goals? Do they even fix management’s needs? Do they help non-union workers?

They don’t affect an economic crisis brought on by wild speculation in the banking and investment sector, or poor management, or global competition. They don’t prevent job loss, or bring back outsourced jobs, or fix broken unions that have not organized for years.

When the union firm takes a dollar-an-hour cut, the non-union company cuts its wages $1.10 and starts chasing the customer to switch vendors.

Concessions need to be looked at case by case, but they do not fix a company’s root problems. In the end concessions should be resisted because they hurt the union community at large as well as the non-union worker.

The second rule for concession bargaining is total transparency. Members need to know what sacrifices management is making. The union needs complete access to the books for verification of management’s claims. If the company is not willing to allow total transparency, there should be no concessions.

ARE CONCESSIONS NEEDED?

Next, the union must test the company’s need for concessions. The Supreme Court has ruled that if the employer claims the inability to pay, the argument “is important enough to require some proof of its accuracy.” The union has the legal right to check the books.

Write a letter asking for a detailed accounting of income, expenses, profits, and losses for the three previous years. Request copies of the IRS W-3 and the IRS 1096, and give assurances of security concerning proprietary and confidential information.

Say that the union isn’t rejecting the opening proposal, but needs to verify the underlying information that demonstrates the company’s inability to meet its obligations. If the union does recommend that members reject, that call should be based on examined facts.

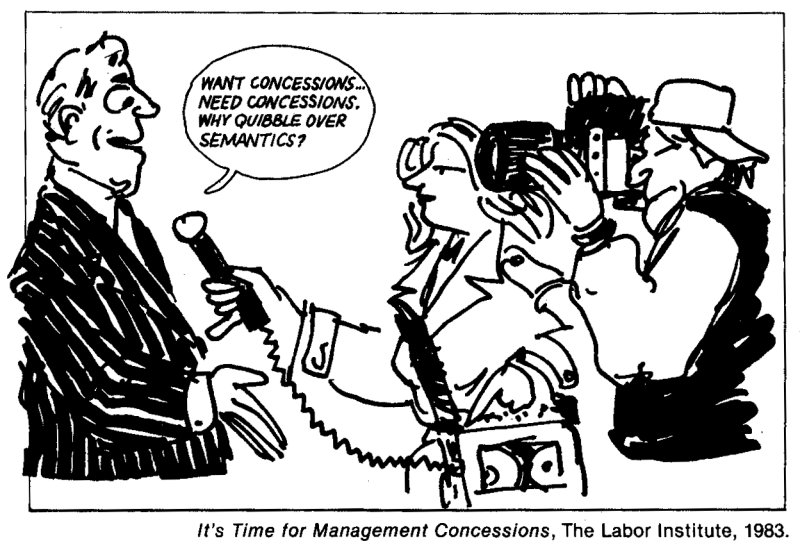

A number of employers faced with a demand to see the books change their tune from “need concessions” to “want concessions.”

The key to good-faith bargaining is a reliable source reviewing the books. The Teamsters, for instance, were in crisis bargaining with YRC, the largest union freight carrier. Rather than use its own people, the union secured an outside consulting firm to thoroughly review YRC’s operations.

The depth review was beyond what the NLRB may have supported, because it looked at every management and non-union salary, benefit, stock holding, and bonus, as well as terminal management, routing of freight, and customer base. The review became a neutral source of data for both sides.

HOW DEEP?

The question then becomes, how deep is the trouble and what kind of fix are we bargaining about? Don’t trust the employer’s math; do your own costing.

In recent bargaining at a Teamster trucking company, the employer said it could not afford the pending health and welfare and pension increase of $40 a week. To break even, the employer was asking for a dollar an hour off the wages.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

The union pulled time cards for the last six months and found drivers were averaging 14 to 20 hours a week in overtime. With overtime, the original proposal would have taken up to $70 a week off wages. Probably a concession of 65 to 70 cents would have put the company at break-even.

The union also pointed out that any reduction in wages reduces taxes: the employer pays less FICA, state and federal unemployment taxes, and workers comp. On a 65-cent wage cut, the company would probably save 12 to 16 cents. In reality, the company needed only a 50-cent cut.

Make any givebacks temporary: in this case, the union made the cut for one year, with the contract popping back to pre-concession wage scales.

THE QUID PRO QUO

No contract should be reopened without getting something for it—this is the union’s card to play when the company says concessions are urgent. Open the contract beyond the money issues the employer wants—go for a total reopener.

As a first condition of bargaining, the union can ask to end the “zipper clause” that precludes either party from raising subjects of bargaining during the life of the agreement.

Make job preservation specific—not just a hope. This is your opportunity to get language that says “there shall be no subcontracting of bargaining unit work while unit employees are on layoff” or “there shall be no subcontracting of work which can be performed by the bargaining unit.”

Fix that grievance definition. Often our contracts narrow the definition of a grievance to what is found inside the four corners of the contract, leaving out the flexibility to grieve and bargain over rapidly changing economic conditions. The union needs to secure the broadest rights to grieve in any situation.

Change your grievance definition to “any dispute over application and interpretation of this agreement and any other dispute over wages, hours, and other terms and conditions of employment.”

GET A WARNING

The WARN Act, which requires 60-day notice of shutdowns, does not provide the cover we assumed it would. It works for employers of 100 or more (excluding part-timers) but not for smaller ones. If your facility is not covered, shutdown-notice language is a must. Insist on language like this:

"The Employer agrees to provide 60 days’ written notice of closing or partial closing. During the 30-day period following the notice, the Employer shall bargain over the closing decision and the effects thereof.

"Failing to reach agreement over new wages, hours, and other conditions necessary to keep the facility open, the parties shall submit any open issues to arbitration."

BIND THE SUCCESSOR

When a company is in crisis the “successors and assigns” language should be strengthened, like this:

"The terms and provisions of this agreement shall bind all sub-lessees, assignees, purchasers or other successors to the business to such terms and provisions, to which the employees are and shall continue to be entitled. The employer shall require any purchaser, transferee, lessee, assignee, receiver, or trustee of the operations covered by this agreement to accept the terms of the agreement by written notice, a copy of which shall be provided to the local union at least 30 days prior to the effective date of any sale, transfer, lease assignment, receivership, or bankruptcy proceedings."

Legally, it is hard to bind the next owner without its consent. The party that is bound is the current employer. Hold his feet to the fire before any sale by forcing a written pre-notice.

This allows the union a chance to mobilize the community and politicians, and seek an injunction to block the transfer if the new owner does not accept the contract.

Layoff and recall language needs to be improved to secure longer return rights. An easy fix for many contracts is to change language to protect members for “12 months, or a period equal to the employee’s seniority, whichever is greater.”

Richard DeVries is a union representative for Teamsters Local 705.