Students Call Adidas on the (Red) Carpet over Sweatshops

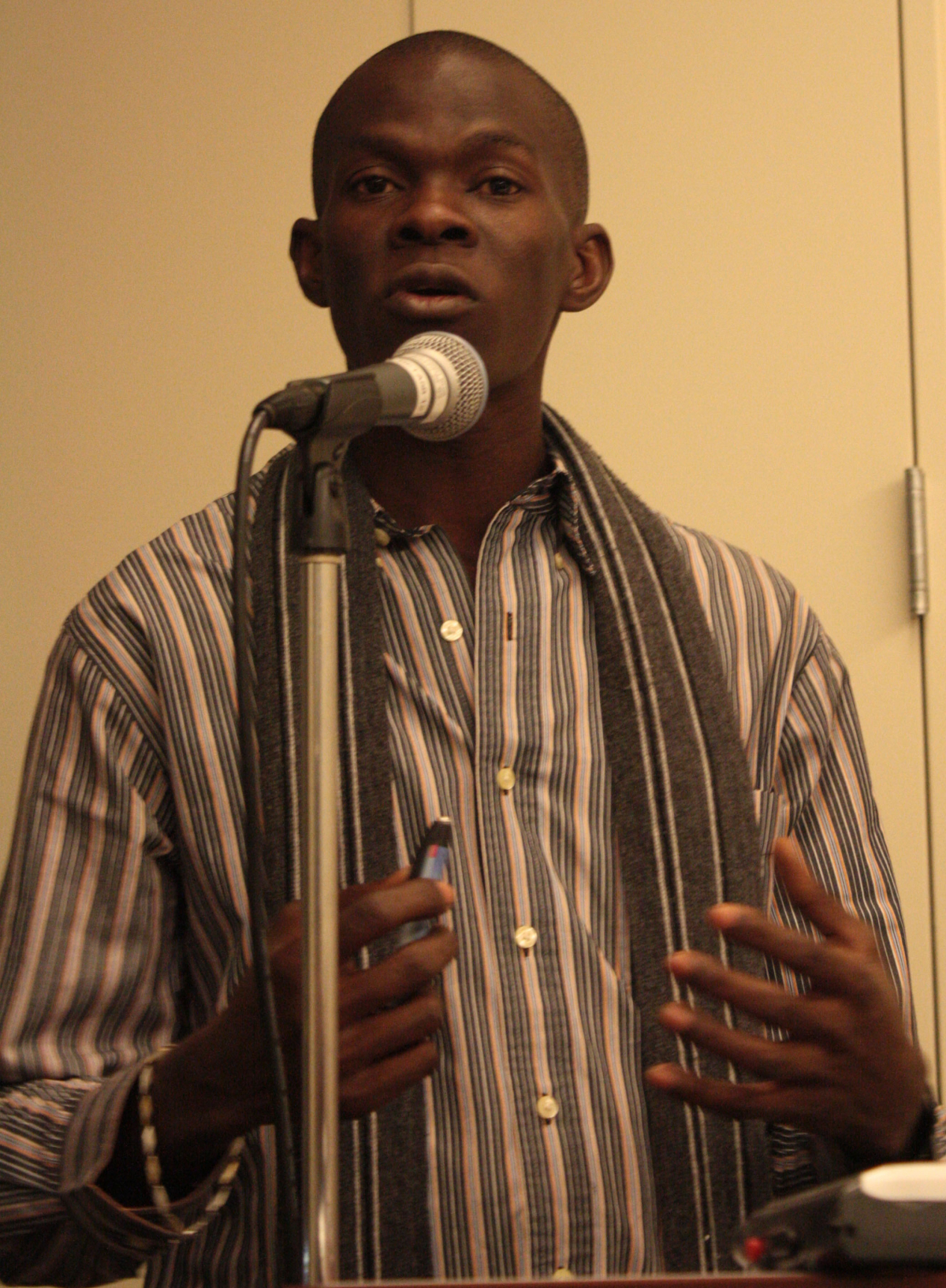

Telemarque Pierre told New York students about working conditions at Adidas's supplier in Haiti, such as pay below the minimum wage. U.S. students are targeting Adidas in an international campaign to raise pay in garment sweatshops. Photo: Bryan Nelson.

Update, April 25: USAS announced yesterday that the workers from the shuttered PT Kizone factory in Indonesia have reached a settlement with Adidas. The terms are confidential, but Adidas will pay "a substantial sum" to the former garment workers.

At New York’s Fashion Week, where Adidas is promoting a high-end clothing line, United Students Against Sweatshops (USAS) is launching a coordinated campaign targeting the sportswear brand. The opening of preteen idol Selena Gomez’s new fashion line was met with a banner from the crowd: “Selena: Don’t Be an Ambassador for Sweatshops.”

Though sweatshop labor is standard throughout the clothing industry, the 2011 closure of a former Adidas supplier was the impetus for the newest USAS campaign. When the PT Kizone textile factory in Indonesia closed that year, 2,800 people were put out of work The company now owes them $1.8 million in severance pay, claims USAS, of which it still hasn’t paid a cent.

Because Adidas neither owned nor closed the plant, which was run by a contractor, the company denies any responsibility for the half year’s pay.

Now workers from a new union that’s organizing workers at Adidas suppliers have come to American college campuses to ask for support. After a kick-off rally in Manhattan this Sunday, union leaders from garment factories in Haiti, Honduras, Indonesia, and Bangladesh will tour the U.S., asking students to push their colleges and local governments to stop buying from Adidas until the company and its subcontractor Gildan shape up on wages and labor rights.

“We, as workers, are looking to you, as students, to pressure the brand,” Honduran union leader Raquel Navarro told an audience of New York University students Monday night. Navarro’s union, Sindicato de Trabajadores de STAR, represents workers at Gildan factories in the Caribbean and Central America.

Gildan, a Montreal-based textile firm, provides blank apparel to Adidas, which then brands it and sells it to NYU and other universities.

Six campuses have already dumped “Badidas” after student pressure, according to USAS. NYU students plan a rally Friday to push their administration to do the same.

Whipsawing Plants against Each Other

Adidas sources from more than 1,200 factories worldwide, doling out its contracts to the lowest bidder. That’s 300 more factories than Nike—though Adidas produces only half Nike’s output—so factory managers have to compete for its business. This model has been great for profits. The Adidas Group (which also owns Reebok) reported record earnings last year.

But the strategy forces garment workers’ wages down under threat of unemployment. When workers in Haiti hint at taking collective action to protect their rights, said veteran organizer Yannick Etienne, “factory owners threaten to leave to Vietnam.”

For an $18.95 T-shirt sold at NYU, a seamstress in Haiti gets 3.5 cents, according to the consumer activist group SweatFree Communities.

At Premium Apparel, a subcontractor in Haiti that supplies Gildan, a group of 18 workers are paid $2.52 for every 72 shirts they make. The multiple layers of subcontracting protect the real employer from responsibility, even though Premium Apparel, supposedly an independent business, sells solely to Gildan.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

In Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Gildan’s suppliers typically pay a daily wage of about 250 Gourdes, or about $5.90, despite the legal minimum wage of 300 Gourdes.

Out of that, workers have to shell out 60 Gourdes for transportation, and breakfast and lunch typically cost 60 and 100 Gourdes. Little is left to take home to their families, said Haitian unionist Telemarque Pierre. His quota of 3,600 shirt sleeves a day is well above what he can reasonably sew in eight hours; he often has to stay two to three hours to complete his quota, but no overtime is paid. Telemarque organized a union in Port-au-Prince three years ago.

Despite the miserable conditions, workers stay because they need the jobs so desperately, said Etienne. A staggering three-quarters of Haitians do not have formal employment.

Navarro’s factory in Honduras pays workers $60 a week, which for a (conservative) 40-hour week comes out to $1.50 per hour.

“In the maquila most girls start between the ages of 14 and 16,” she said, “and a day past 30 they are considered worn out, and fired.”

Laws Unenforced

Labor laws such as minimum wage and freedom of association often go unenforced, workers from Haiti and Honduras said, because their governments are so desperate to keep foreign capital—and the dismal jobs that come with it—from leaving for cheaper labor. In fact, much apparel production takes place in designated “free trade zones” exempt from possible labor protections.

“The people who have sworn to protect us, won’t,” Etienne said.

So the workers are protecting themselves—and looking to international allies, including United Students Against Sweatshops, for support.

Over the past decade, USAS and its allies have pressed many U.S. universities—and, through them, the apparel brands—to reveal the locations of apparel factories, accept labor standards and outside monitoring of factories, and join the sweat-free Designated Supplier Program.

In the new campaign, students are breaking down the supply chains that protect multinational corporations like Adidas at the expense of their workers, to aid a new international unionism. With the help of consumers, these fledgling unions can make a place for dignified labor under globalization.

Andrew Elrod writes for NYULocal.com. He studies history.

NOTE: This article has been updated to correct an error. The name of Navarro's union is not STAR but rather Sindicato de Trabajadores de STAR, or SITRASTAR.