How New York Taxi Workers Took On Uber and Won

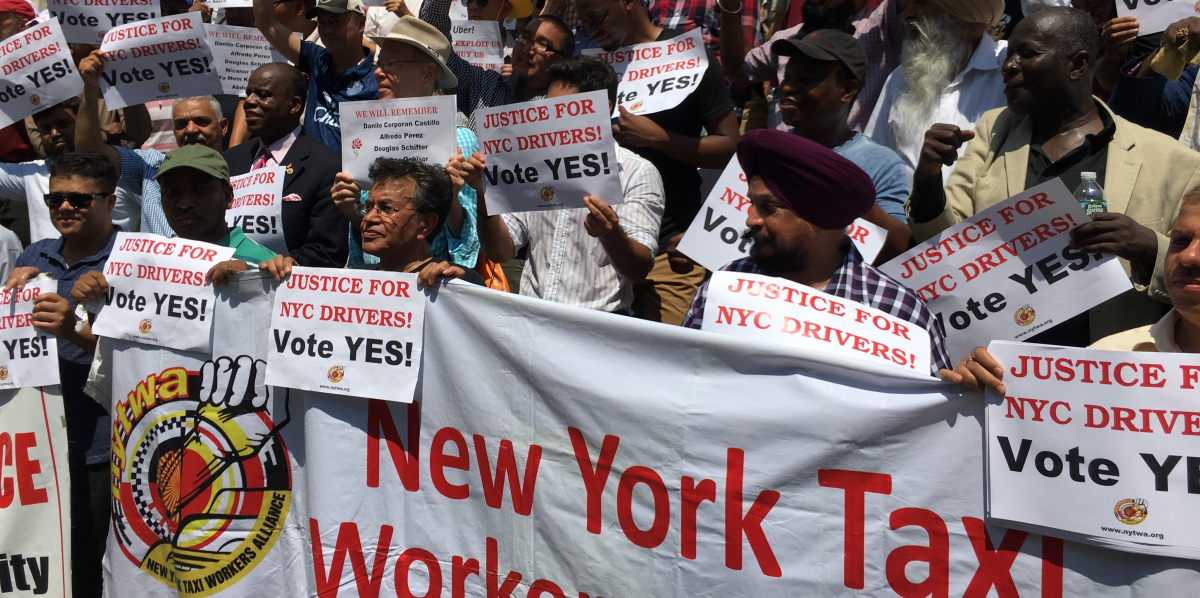

New York is the first city to mandate a cap on app-based, for-hire vehicles, and the first to mandate a minimum wage for Uber and Lyft drivers. Photo: Chris Brooks

This summer, the scrappy union representing 21,000 taxi and for-hire vehicle drivers in New York City scored two groundbreaking victories against the world’s most valuable start-up company.

If Uber was looking for a fight, it found one in the Taxi Workers Alliance.

The state’s Unemployment Insurance Appeal Board ruled against Uber in July, stipulating that its drivers are employees eligible for unemployment insurance. Misclassifying drivers as independent contractors has allowed Uber and Lyft to evade payroll taxes for hundreds of thousands of drivers across the country and to cheat those drivers of overtime and minimum wage protections—not to mention the right to organize a union.

The unemployment ruling has particular significance because there’s such a glut of app-based vehicles in the city— the number swelled from 25,000 in 2015 to 80,000 in 2018, with an average of 1,700 more cars added every month. Uber drivers can now demand unemployment when there aren’t enough passengers to go around, and the state is gearing up to audit Uber to determine how much it owes the unemployment fund.

Weeks later, the Taxi Workers and their allies won legislation making New York the first city to mandate a cap on app-based, for-hire vehicles, and the first to mandate a minimum wage for Uber and Lyft drivers.

The one-year cap will hit the pause button on adding any more drivers while the city’s Taxi and Limousine Commission studies the number of vehicles on the road and the glut’s impact on traffic, drivers’ livelihoods, and taxi availability in different areas of the city. After the year is up, the TLC may pursue further regulations.

The city council has mandated that Uber and Lyft drivers should earn a minimum of $17.22 an hour—the independent-contractor equivalent of $15 an hour, after taxes and expenses. Just how that gets implemented will be hammered out in TLC rulemaking. The TLC is also authorized to regulate minimum fares, which could level the playing field to stop app companies from manipulating prices to undercut taxis.

Vehicles with wheelchair access are exempt from the cap, since fewer than 1 percent of for-hire vehicles in New York City are wheelchair-accessible. The Taxi Workers Alliance worked hand in glove with Taxis for All, a coalition of disability rights groups.

“So many people in the labor world said, ‘You can’t organize these workers and you can’t beat back these companies,’” said Taxi Workers Executive Director Bhairavi Desai. “But here we are, a motley crew, a grassroots, worker-led movement, and we defeated them because we never gave up.”

The employer-funded Independent Drivers Guild, which was created in a secret agreement between Uber and the Machinists union, also claimed victory—though initially it opposed the cap.

UNDERWATER LOANS

Many major cities issue set numbers of taxi medallions, which authorize vehicles to pick up passengers. By constraining the number of taxis on the road, cities can reduce congestion and add to city revenue through the sale of medallions.

Then came Uber and Lyft. As the number of app-based vehicles skyrocketed, the value of medallions plummeted. The same thing has happened in San Francisco, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Boston.

“A lot of owner-operators borrow money to buy the medallion,” said Sonam Sherpa, who has driven a New York taxi for 20 years. “Four or five years ago the medallions were worth $1 million. Today they are worth $200,000. That shows you the impact that Uber has had on taxis.”

Among New York taxi drivers who own their medallions, 80 percent are underwater—meaning their medallions are worth only a fraction of their outstanding debt.

One of those owner-operators was Kenny Chow, who had been on the road for a decade. Chow found himself stuck paying back a loan that totaled more than double what his medallion was now worth. Meanwhile he was getting fewer and fewer fares, thanks to the explosion of app-based drivers.

“He kept making less and less money and eventually just didn’t have enough to take home,” said Kenny’s brother, Richard Chow.

In May, he took his own life—one of six suicides by city taxi drivers in the first half of this year.

OVERSATURATED MARKET

The majority of yellow-taxi drivers don’t own medallions, but work for fleets, where they lease medallions for a day or a week at a time.

Fleet drivers have a lot in common with app drivers. They too are generally treated as independent contractors, so they have to cover expenses, health insurance, and taxes out of what they earn. If they don’t pick up enough fares, they can end a 12-hour shift with less money than they started with.

All types of drivers are suffering from the oversaturation of the market, not to mention the ever-worsening traffic congestion.

The apps’ business model relies on drivers’ responding quickly to customer demand. That requires a large pool of drivers driving around waiting for a trip. According to a report from the New School, Uber and Lyft drivers spend 40 to 50 percent of their time idling without a passenger.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Uber has a history of manipulating fares to undercut taxis or make a quick killing. “If there is nice weather they reduce the price,” said Sherpa, “and in bad weather, they raise it. Unlike with taxis, there are no fixed fares.”

By the Numbers: New York City’s For-Hire Vehicle Industry

- Number of Uber and Lyft vehicles in 2015: 25,000

- Number of Uber and Lyft vehicles in 2018: 80,000

- Number of taxis in 2018: 13,600

- Total number of for-hire vehicles licensed in 2018, including livery and other types: 130,000

- Percentage of app-based drivers earning below the minimum wage: 85

- Percentage of app-based drivers who qualify for Medicaid: 40

- Value of taxi medallion in 2013: $1 million

- Value of taxi medallion in 2018: $200,000

- Percentage of taxi medallion loans that are higher than the value of the medallion: 80

- Uber’s most recent valuation: $72 billion

“The overwhelming majority of Uber, Lyft, and app-based for-hire vehicle drivers are immigrants, and two-thirds of them are driving full-time, but 85 percent don’t earn a living wage,” said New York City Councilmember Brad Lander in a hearing. “Forty percent of them have incomes low enough to qualify for Medicaid.

“The 500 percent growth in cars is what has made that happen.”

CLASHING CAMPAIGNS

Uber is one of the world’s most highly valued private firms, with a valuation of $72 billion earlier this year, and is planning an initial public offering in 2019. But its valuation will depend on how the company fares under increased regulatory scrutiny. There’s a reason Uber employs more lobbyists than Walmart.

If Uber didn’t misclassify drivers, the New School report found, it would be the largest for-profit employer in New York City, which is its largest U.S. market.

When the Taxi Workers’ campaign gained momentum, the company went on the attack, spending millions on a public relations drive to claim that the cap on vehicles would make the service less reliable and more expensive.

On social media, in radio ads, and at company-organized rallies, Uber spokespeople including Bernie Sanders’ former press secretary Symone Sanders and the Reverend Al Sharpton praised the app as a solution to taxi drivers’ turning down Black passengers.

But the Taxi Workers waged an equally aggressive campaign in the streets. The union organized 30 actions in the six months leading up to the City Council vote.

They collected 4,000 postcards demanding that the mayor address the crisis facing drivers. They held vigils in honor of the drivers who committed suicide. They rallied outside city hall.

The union admits that more needs to be done to stop race-based refusals. It also supported the creation of an “office of inclusion” in the TLC, which will require taxi drivers to attend racial bias training and provide more resources to investigate rider allegations. Taxi drivers found to have denied rides based on race can be fined and have their licenses suspended.

In a nine-point plan to end race-based refusals, the Taxi Workers have proposed that the TLC’s license renewal system should require racial justice training that highlights the role of transportation unions in fighting for civil rights. They also proposed strengthening apps that drivers can use to find passengers in the underserved parts of the city, outside Manhattan.

The union charges Uber with cynically pitting communities of color against one another. More than 90 percent of both taxi drivers and Uber drivers are immigrants. The majority come from the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh.

“Neither Uber nor the yellow cab industry has been able to show that you can provide a good service to the public, fill transportation deserts, and maintain good working conditions for the drivers,” said Desai. “Neither model has worked out, but that is what our organizing is pushing for.”

You must log in or register to post a comment.