Building an Army to Fight Runaway Inequality

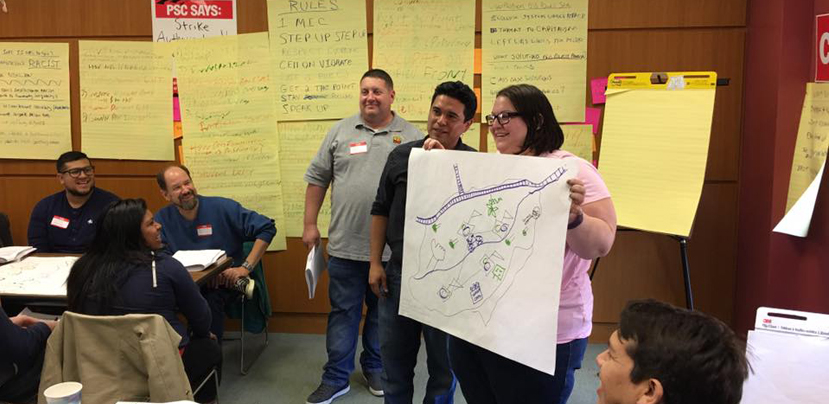

The Runaway Inequality program has reached hundreds of union members and community activists in a dozen states, helping fuel the growth of local coalitions. Photo: Sustainable Staten Island

How can unions help create a social movement to take on Wall Street’s economic and political dominance?

That’s the question that the Communications Workers (CWA) are tackling with labor educator Les Leopold. The training program they’ve put together, based on his book Runaway Inequality: An Activist’s Guide to Economic Justice, has already reached hundreds of union members and community activists in a dozen states—where it’s getting rave reviews and helping fuel the growth of local coalitions.

Participants get a crash course in the rapidly growing gap between the super-rich and ordinary workers. They learn how the ever-growing power of hedge funds and private equity managers has put our government in thrall to the billionaire class and contributed to environmental devastation, racial discrimination, an outsized prison population, and plummeting wages.

“This training is a direct result of Occupy Wall Street,” says Verizon tech Ray Ragucci of Local 1102 on Staten Island. “Occupy had the message, but I don’t think they were organized well. So now what we’re trying to do is to keep it going and turn it into a real solid movement.”

“People are hungry,” says Leopold. “They’re trying to understand the economic chaos around them. It’s hard for them to put the pieces together.

“The training is about showing the interconnectedness between all the issues that face people, and showing how they’re tied together through this runaway inequality, financial strip-mining model.”

By building a common understanding of the problems we face—that, as one chapter of the book puts it, “everything is connected to everything else” and an injury to one is an injury to all—the program aims to build a cross-movement alliance that can take on the economic and political elite.

“Right now, we’re all stuck in our own individual thing,” says Ragucci. “The unions do what the unions do, and the Fight for 15 does what they do, the environmentalists do what they do, and so on. It’s all about breaking out of that. Then it’s like back in the ’50s and ’60s, when you had the civil rights movement—it was all different groups getting together and backing each other up.”

STRUCK A CHORD

This program developed out of a six-month training that a group of 20 Verizon workers went through in 2015. Whenever CWA trains members on any topic or skill, the union makes a point of including some political education too, with the goal of “building a broader political analysis,” says Margarita Hernandez of District 1, one of the coordinators of the program.

So once a month, before afternoon sessions on organizing and political outreach, the group spent the morning with Leopold, who presented material from his book.

“We were all unanimously like, ‘This is what we need,’” says Ragucci. “We felt if we could bring this stuff to our members and educate them, it might trigger some sort of movement.”

And the members decided that they—not Leopold or CWA staffers—should be the ones leading the classes for their co-workers. “They pushed, they called, they emailed,” says Hernandez. “At every single training meeting, every month, that was part of the conversation.”

So the union worked with Leopold to put together a three-day “train the trainer” workshop in January 2016, where participants learned to facilitate Runaway Inequality workshops in small-group settings. Activists from the immigrant worker center Make the Road New York and the community organization Citizen Action attended too.

“We went over it, we practiced it, and we did it—and they sent us out into the world,” says Dennis Dunn, a Verizon FiOS tech and chief steward with Local 1108 on Long Island. Now dozens of rank-and-file trainers regularly lead the workshops for other union members and community activists.

‘DOING IT OURSELVES’

Each full-day Runaway Inequality training holds 20 to 30 people. At tables of five or six, participants work together to answer various questions.

In one activity, groups are asked how much they believe the average CEO of a large company makes, versus the average worker. “Most people get that there’s a pretty big gap,” says Ragucci. “But then when they see the number, they’re usually pretty off.” The real ratio is 844:1.

Groups are also asked how much they think CEOs and workers should make. “Whether you’re a Democrat or you’re a Republican,” says Ragucci, “we all think the CEOs are making way too much money.”

In another, they’re asked to list off as many U.S. social movements as they can—and the trainers highlight that some of the most important periods of union organizing coincided with outbursts of social movements, in the 1930s and 1960s.

“What I love about doing these workshops is it’s not a lecture, so you’re not losing people,” says Dunn. “You’re forcing small groups to talk and think, and then as facilitators we just take the feedback and keep it moving.”

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

“A lot of the success has to do with the methodology of it, and that members are leading it,” says Hernandez. “Because it’s the nurse from your local hospital who you work with, or the phone guy at your garage who you see all the time, it really changes the conversations that happen in the room and how comfortable people are in speaking up.”

That familiarity can help facilitate hard conversations around race and immigration, both covered in the program. Participants look at examples of how bosses have used race to divide workers, and learn about the wealth gap between races—including how even Black college graduates have much less wealth on average than white high school dropouts.

“It’s not like the teacher-student type of thing,” says Ragucci. “It’s more of a brotherhood. And it helps the union, too. You have more resources at your disposal. Now instead of our district having to hire 10 more people, we’re doing the stuff ourselves.” (For more on popular education methods, see Chris Brooks’s interview with Susan Williams of the Highlander Center, Organizing to Learn, Learning to Organize.)

MIXING IT UP

Ragucci led the training with members of his own local who work at the toll collection agency EZ-Pass, during their recent contract negotiations. Dunn has led it for locals on Long Island and in Boston, and did a shortened version at the union’s national wireless sector conference last summer.

CWA held a second train-the-trainer last year for members in states in the middle of the country. A third is planned for April.

Besides teaching their fellow CWA members, trainers have been volunteering to lead sessions on their days off for members of other unions and community groups. For instance, Ragucci has done a few trainings for members of Sustainable Staten Island, a coalition that emerged from the Verizon strike and includes worker centers, the New York State Nurses, the faculty and staff union at the City University of New York, and environmental organizations.

Many of the first corps of trainers spent 49 days on strike at Verizon last year. “Without the help of outside organizations and public and political pressure, how successful would our strike have been?” Ragucci asked. “That’s what we’re trying to do—make alliances with other groups outside of our union, trying to find the connection and how we can fight together.”

“They’ve been using the program to build alliances in their areas that weren’t really happening before,” says Hernandez, “or that were happening in a more transactional way, but now they’re building deep relationships and developing actions together. It made them more movement builders, rather than just thinking about how to get bodies out to an event.”

Joseph Mayhew of CWA Local 1103 has pulled together trainings that mingle members of unions, community organizations, and faith groups through the Westchester-Putnam Central Labor Council, north of New York City.

At the first training, “everybody sat with everybody they already know,” says Mayhew. “So the first thing we did is we moved everybody around to make sure every table had somebody from labor, somebody from community, and somebody from faith.”

Mayhew says this alliance-building paid off during the fight against the Trans-Pacific Partnership. “I remember showing up at a member of Congress’s office who I’ve seen many times before, and his chief of staff said that what was most impressive was that we showed up with all these other people and were coordinated.”

ARMY OF EDUCATORS

After the Verizon strike, Dunn was invited to fly across the country to speak at a conference of AFSCME Local 3299, the union of service workers at the University of California campuses and hospitals. He brought copies of the Runaway Inequality book and pitched the trainings there.

“They were inspired by the strike,” says Dunn. “But I said, ‘We gotta change things together. We gotta break down the silos. We gotta get our regular members involved, not just the board.’”

Dunn has a vision: “How cool would it be if a CWA member, an ATU member, and an AFSCME member are at an SEIU conference, and they have a couple of workshops that people can wander into? But there’s a resistance from labor, and cracking that is hard.”

Leopold is already working to spread the program. He’s sold thousands of copies of his book to other unions, including the Steelworkers, National Nurses United, and the New Jersey Education Association, and has trained members of other groups to offer the workshops too. On a recent trip to the Bay Area, he led a training with the Sierra Club, the Steelworkers, and CWA, which even took up the thorny question of alliance-building between environmentalists and labor.

Now he wants to open it up to the public at large. He’s planning a series of two- to three-day train-the-trainer sessions across the country, wherever he can find 20 or 30 interested people. The aim: to build an army of educators. “The model behind this is the Populists of the 1880s, who fielded 6,000 educators,” he says.

But in the meantime, the program is even helping to build links within unions. “It’s broken silos within CWA,” says Dunn. “I wouldn’t even know who these guys were—but now they’re like my brothers, like another family.”

[If you’re interested in becoming a Runaway Inequality trainer or bringing the training to your union or organization, fill out this form, or email dan[at]labornotes[dot]org. Or sign up at runawayinequality.org, where you can also buy the book ($15).]