What Vermont Paraeducators and School Bus Drivers Learned When They Almost Went on Strike

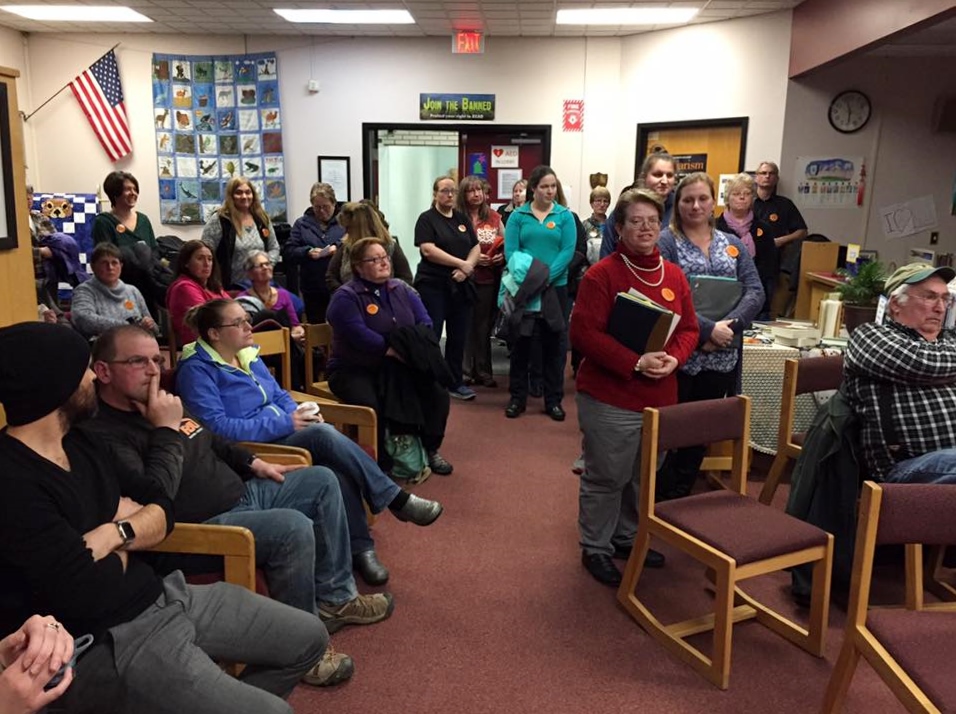

Paraeducators and school bus drivers rebuilt a formerly passive union, changed the power dynamics in bargaining, and built towards a successful strike—and learned four key lessons along the way. Photo: Emma Mulvaney-Stanak

What do you do when your employer suddenly turns hostile? After years of relatively friendly labor relations, in 2015 the school board in rural Brandon, Vermont, shut down negotiations and imposed its terms: higher health care costs and minimal raises.

The school board assumed that support staff would never strike. No school staff union in Vermont had ever struck on its own, without teachers. Meanwhile the sister union representing teachers agreed to a rollover contract. The teachers kept their distance from staff negotiations, not wanting to hurt their own relationship with the board.

The union of 100 paraeducators and school bus drivers was caught off guard. On top of “open hostility from the community,” said Loretta Johnson, a paraeducator and the union president at the time, internally the union was dealing with “a lot of fear and minimal member involvement.”

Another obstacle: the bargaining unit included two groups of workers, paraeducators and bus drivers, who had diverging interests. Fewer than half of the bus drivers were union members. Health insurance was the largest sticking point in negotiations, but most drivers didn’t take the district’s insurance. Meanwhile the paraeducators, who offer specialized support for students with behavioral and learning challenges, were nearly all union members.

But school support staff didn’t let these challenges stop them. This is the story of how they rebuilt a formerly passive union, changed the power dynamics in bargaining, and built towards a successful strike—and learned four key lessons along the way.

SURPRISE STRIKE VOTE

Nearly two years after bargaining began, the Rutland Northeast Education Association finally formed an organizing team that set out to mobilize members and save face in negotiations—short of striking.

A meeting on what to do about the stalled bargaining attracted a big turnout, nearly 95 percent of members. Leaders presented a routine motion to symbolically reject the imposition and move forward to bargain the next contract.

But members had had enough. They felt mistreated by the board, outraged over their frozen wages and the uncertain status of their health care, and disrespected after months of working with no contract. Members amended the motion to call for an immediate strike. It passed with 87 percent of the vote. The yes voters included many bus drivers.

Shocked, union staff and local leaders scrambled to build the basic infrastructure for a strike. A week later, the school board caved and settled a contract, replacing the imposed terms.

- Lesson #1: Trust democratic decision-making. Trust members. They’re not a blank slate; they can analyze risks and make complicated decisions. Local officers and union staff should avoid presenting members with a pre-scripted decision or plan. If we really want stronger unions, we must allow room for it to get messy and unpredictable.

DISUNITY WITH TEACHERS

Undeterred, the board pushed similar proposals even harder the next year. With a new state mandate requiring major changes to insurance terms and costs, every school district and union lined up contracts to expire in June 2017.

The new plans offered cheaper premiums—but for the first time, employees would face out-of-pocket expenses and high deductibles. Some expenses would be reimbursed, but for support staff already living on tight budgets, paying upfront would be tough.

This time the union tried to get organized earlier. Leaders sought out the most respected members among bus drivers and paraeducators in underrepresented schools to join the organizing team, and adjusted meeting times to accommodate members’ shifts and second jobs.

The team tried out brand new tactics untested by Vermont-NEA. For instance, members held informational pickets on their own—without teachers. They phonebanked NEA-generated lists of likely parents and pro-education voters to talk about paraeducators and bus drivers’ role in the schools and the status of bargaining. They asked parents to show up at board meetings and urge the board to settle. They also mobilized their own members to attend board meetings and tell their personal stories of economic struggle.

The organizing team decided to delay its efforts, to wait for the teachers’ bargaining to catch up. If the board imposed again, unifying the two unions would build power. Sure enough, in June the board did impose again.

But when the time came to unite forces that fall, the teachers avoided merging organizing teams and declined to actively support the staff’s tactics. Some teachers continued to believe the board would ultimately favor them—and even if not, that they would be better off organizing on their own.

- Lesson #2: Solidarity takes time and conscious relationship-building. Solidarity is not a machine that can be reliably turned on or off, nor can it be assumed. Though these teachers and support staff are in locals of the same state union, building a stronger relationship requires regular cultivation, something the RNEA is continuing to work on. Later, as they built toward a second strike deadline, the local unions began to attend each other’s leadership meetings, communicate regularly, and present a more unified front to the board and superintendent. To sustain these new relationships, those practices must become everyday norms, not just what happens when either union is in crisis.

BRING THE KIDS TO THE MEETING

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

RNEA pushed on with its organizing. “We experienced unprecedented member attendance at meetings and solidarity actions,” said Johnson, “mainly because they were extremely frustrated due to delays, bargaining dynamics and a second imposition. They were ready to be more aggressive.”

To handle complicated shift schedules, RNEA began scheduling duplicate meetings—one after school and another in the evening, with pizza and a standing invitation to bring kids along. After every meeting, the union sent out updates via home emails, mailings, and handouts in school mailboxes, repeating the key points and the “asks” for how members could participate. Eventually the organizing team phoned every member and non-member.

The mailing and phone lists also included rank-and-file teachers who lived in the district. This direct communication generated some teacher support.

Bus drivers and paraeducators attended local events such as the family-oriented Harvest Festival. They called high-profile community members—faith leaders, business owners, heads of the Parent Teacher Organization—to ask for support. As a result of these calls, the union teamed up with the Vermont Workers’ Center, the local nurses union, and the lieutenant governor to organize a town hall on the need for health care reform.

By Thanksgiving, the organizing team was divided. Some had felt ready to strike for months—while others still feared the risks: How long could members go without wages? Have we built enough power to win? After much deliberation, leaders agreed the full membership should decide the next step.

Members met in December. Tension filled the room as drivers and paraeducators weighed the risks. With 85 percent of the members present, the vote was 82 percent yes authorize a strike.

- Lesson #3: Challenge assumptions. The organizing team used time-tested tactics, but also broke the mold by taking seriously the possibility of a strike. Union staff and local leaders worked through many fears about whether a support-staff-only strike would be viable. By the second time they voted to authorize a strike, members felt ready to act.

‘WE’RE YOUR NEIGHBORS’

In the days leading up to the strike, the superintendent prepared to hire temporary replacements. The union accepted that schools would remain open. Still, members worked to make hiring scabs as difficult as possible.

They reached out to education unions within a 100-mile radius to request that substitutes refuse extra work in the Brandon area. They asked local teachers to lend support by refusing to work outside of their teaching duties.

The union knew its strongest leverage points: student transportation and special education rules. The organizing team proudly confirmed that half the bus drivers in the bargaining unit had agreed not to cross a picket line, whether they were union members or not.

Vermont has a shortage of certified bus drivers, even for private bus companies. Legally every employee must submit to a criminal background check, which takes days. The district struggled to find, train, and screen enough drivers before the strike—though it denied this publicly.

Scab drivers would be strangers to students and unfamiliar with the routes, raising safety concerns. Special education teacher caseloads would skyrocket, and students would suffer without paraeducators. The organizing team made sure to share this critical information with parents before the strike.

Union members leafleted door to door, sent letters, and phoned parents and voters. They focused on affordable health care, living wages, and the message, “We’re your neighbors,” since 80 percent of members lived within the district. These arguments resonated with people—especially when they learned that the board was looking for scabs, and that the union’s settlement proposal would cost less than one-third of one percent of the school budget.

The teachers union was finally becoming more supportive, as its own negotiations heated up. Teachers began to donate supplies for strike headquarters. They held meetings to prepare members to identify potential grievances if they were asked to do staff work during a strike.

In the end, a federal mediator intervened. The union and the district signed a settlement two days before the strike date. Staff won a decent wage increase and a fair split on employer-employee out-of-pocket expenses, including a debit card that workers could use upfront for health expenses.

- Lesson #4: Rural organizing presents challenges and unique strengths. Members in small towns can be hesitant to share their stories of economic hardship with their neighbors, but direct contact with neighbors and parents proved to be the most powerful tool. Also, it’s tough for the boss to replace school employees in a rural area on short notice. Keeping schools open during a strike would have meant understaffed classrooms, gaps in bus schedules, unfamiliar drivers, and special-ed staffing shortages—which could all spark public outrage.

Emma Mulvaney-Stanak is a former Vermont-NEA statewide organizer.