How the 'Wentzville 41' Defied GM and Saved Seniority

When 41 Missouri auto workers took a stand against job rotation, they were fired in the middle of the night—but not for long, after support flowed in from around the country. “Two things enable you to stand strong: faith and guts,” one said. All photos via Facebook, courtesy of the author.

Forty-one Missouri auto workers stood up for seniority in March when they defied orders to work outside their usual jobs—showing General Motors they weren’t about to tolerate being walked all over.

To understand their story, you must first grasp the environment in which it was born. Most GM plants use job rotation, a practice where members bid into a team, then rotate during the week among the team’s several jobs.

But United Auto Workers Local 2250, in the St. Louis suburb of Wentzville, is old-school, hard-nosed—the last of a dying breed. We’re usually the last plant to incorporate the company’s “newest” programs to undermine workers’ rights, overload jobs, and cut the workforce.

So the local hasn’t yet been completely converted to the company’s vision of manufacturing. For instance, when the UAW adopted the tiered wage system in 2008, 2250 was one of two locals in the country that rejected it.

Local 2250 believes that job rotation undermines seniority—and in Wentzville, seniority is king. The local has fought the practice head-on. When members come to work, we own one job and one job alone.

LAST FREE WEEKEND

The story of the 41 began a few days before the plant was scheduled to go into “critical status”—which basically means GM can set whatever hours it wants, to hit production goals. The contract goes out the window.

Local 2250 auto workers are no strangers to long hours. We’ve worked 10- to 12-hour days for the last three years.

That’s because we build hot items: the new Colorado and Canyon (2015 Motor Trend Truck of the Year) and the Chevrolet Express and GMC Savana (full-sized cargo van). The mid-sized truck is the only American-made model in the segment. The van is a hot ticket with U-Haul and other commercial fleets.

To accommodate the orders, Wentzville recently went to three shifts. Employment here has almost tripled.

As the weekend approached, workers prepared to spend our last bit of freedom with family and friends before hunkering down to work seven days a week for 90 days straight.

But as first shift was released on Friday, March 20, news spread that third-shift body shop—both new body (truck) and old body (van)—would be called in to work that night.

Reluctantly, they showed up. Everyone wanted to get the shift over with and return to their last weekend off.

As the truck body workers arrived, they noticed their work area was already occupied by skilled trades workers doing plant maintenance. Management group leaders told workers to gather at the team center for announcements.

A mistake had been made, the group leaders said. Maintenance had been scheduled. So the truck employees would be moved to work on the van instead.

In other words, after being called in for mandatory overtime, the workers were being forced to rotate jobs—a practice not allowed by the local contract, and one the local had fought for years.

WORKERS REFUSE

The workers took a stand. “I showed up to work, willing to do my job,” one said. (Names are being withheld here because the company has already reprimanded workers for speaking to the media.)

“I should be doing what I’m trained to do. [The company shouldn’t be] flying by the seat of their pants, finding something to validate me being there, when I could be home with my family.”

Union reps told all temps and new hires still on probation to do as they were told, so as not to jeopardize their employment. But 41 seniority workers stood together and told the company “no.”

“Though our product is needed and we value our customers,” one worker said, “that doesn’t give the company the right to disregard our agreement and walk all over workers and their families.”

Management sent disciplinary labor reps to threaten workers and give direct orders, meaning, “Do as you’re told or be disciplined.” The game was afoot.

Managers, blowing steam out their ears, walked all 41 to the front labor office, sat them in a holding room, and called in the company’s ax men.

The disciplinary hearings proceeded from 1 a.m. to 5 a.m. One by one, the 41 were marched into the labor office and charged with violating Article 71 of the national agreement, “work stoppages.”

One by one, the workers replied that they weren’t refusing to work, would gladly have done the jobs they were trained in, and didn’t support any stoppage. It was the company that had fumbled the ball.

One by one, they were fired.

WORD SPREADS

News of the standoff spread quickly, mostly through the UAW’s strong Facebook networking pages.

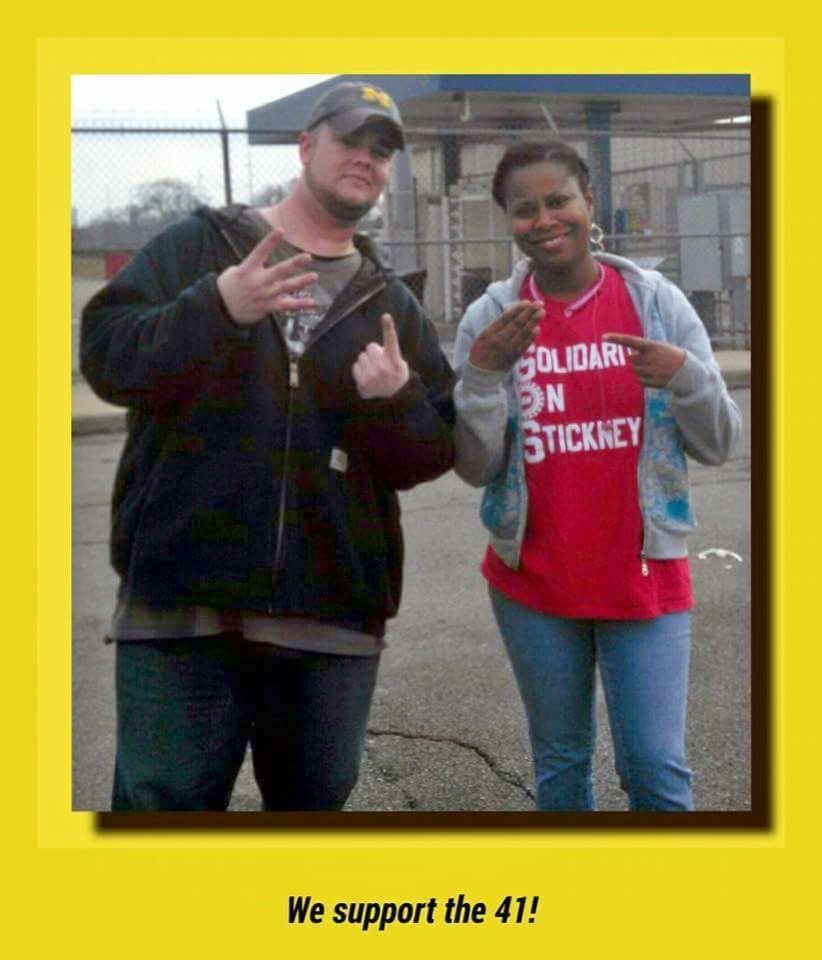

Solidarity for the 41 grew—starting at the Local 2250 page, and then the Autoworkers page, which soon brimmed with photos of workers showing their support on signs and T-shirts. Messages of support flowed in from New York, Wisconsin, and Texas, strengthening the workers’ resolve.

This was quite the rogue act. Most plants practice job rotation; workers pretty much do what they’re told. But even though some locals were confused by the action, they didn’t falter. They stood together.

Seeing that the movement was gaining traction, and not wanting to make martyrs of the 41 in a contract year, the company was quick to settle. Normally the company would drag everyone through the mud for a few months—but this time, workers were off the job less than two weeks before GM came to the table to discuss what could be done to bring them back.

The night before the fired workers would have lost their health benefits, local and international union reps reached an agreement with the company.

‘FAITH AND GUTS’

All 41 were brought back to work, kept their specific jobs, and were put on 18 months’ probation. No back pay was awarded up front, though the union says it will continue to seek it.

The union reluctantly agreed to a new alternative break schedule that allows more production per shift. Now workers have to wait a long time between two relief breaks, because their lunch has been moved to the end of the day. They can take it off-site, which means getting home 30 minutes early—but at the cost of losing what previous generations had fought for, a real lunch.

“Critical status” has been suspended, and an alternative schedule adopted. Sundays are no longer mandatory, though they are “subject to change” in case of breakdowns or production loss. The new schedule follows “Plan A” of the national agreement, so each shift will work eight-hour days and two out of three Saturdays.

So far, 90 new jobs have been added to the body shop to make up for the worker shortage that got the company into the mess of forcing rotation in the first place.

Though neither side is completely happy, each side got the main thing it wanted: the 41 workers are back on the job, and production has resumed in an organized fashion. All aspects of the deal will be up for negotiation again this September, as the two sides begin to bargain a new national contract.

The real story was the show of solidarity. Threatened with losing their jobs, the workers put their paychecks on the back burner to stand up for their principles, protect other workers’ rights, and challenge the company’s “we can do whatever we want” attitude.

“In a situation like this, two things enable you to stand strong: faith and guts,” one Wentzville worker said. Thankfully, across the nation, we had both!

Arthur George is the pseudonym of a Wentzville GM worker and UAW Local 2250 member.