Give Your Union a Dues Checkup

Click graph to pop up enlargement.

Dues are the bricks and mortar of our labor movement, but in many unions dues are a taboo subject. From per capita taxes to initiation fees and special assessments, rank-and-file members rarely get a full picture of their own union’s dues structure, much less a sense of what’s happening across the labor movement as a whole.

WIDE VARIATION

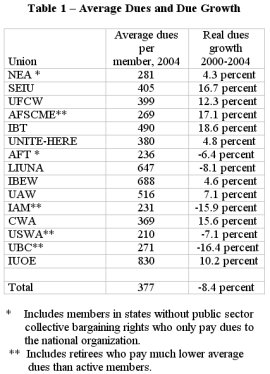

Data from the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA) provide the only national picture of union dues in the country. Table 1 shows the average annual dues per member for the 15 largest unions in 2004 (the latest year with complete data). Average dues are calculated from local union collections. But even these figures aren’t the whole story. Reporting requirements have been streamlined in recent years, making it impossible to separately identify big ticket items like special assessments.

There is tremendous variation across major U.S. unions, ranging from a high of $830 a year for the Operating Engineers (IUOE) to a low of $210 a year for the Steelworkers (one of the unions where retired members pay nominal dues and pull down the overall average).

Dues are much higher in the building trades than in most other unions, with the Electricians and the Laborers ranking second and third in terms of average dues. But even unions with a reputation for organizing low-wage workers, most notably the Service Employees (SEIU) and UNITE HERE (which represents hotel and restaurant workers), have higher than average dues.

RAISING DUES FOR WHAT?

Dues have been going up in most large unions since 2000 (see Table 1). Adjusted for inflation, the biggest increase among major unions was in the Teamsters, where dues went up by almost 20 percent. But the Teamsters were not alone raising dues significantly in recent years. AFSCME, SEIU, CWA, UFCW, and the IUOE all posted double-digit dues increases between 2000 and 2004.

In some cases, these increases came as part of national organizing initiatives, like the New Strength Unity plan SEIU adopted at its 2000 convention. Under this program SEIU locals raised dues $4 a month every year for five years straight, with the increased revenues channeled into new organizing.

In other unions the dues hikes were a reaction to internal or external events. For example the Teamsters dues hike came in response to a budget crisis inside the union, while the UFCW belatedly raised dues following the 2003-2004 Southern California grocery strike.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

“Dues have been going up pretty steadily over the last couple of years,” remarked Russ Blunden, a Meijer’s grocery stocker and member of UFCW Local 951 in Sterling Heights, Michigan. “People are upset…The way the union is run my co-workers feel powerless. They just throw their hands up and say, ‘Why bother?’”

In the case of the Operating Engineers it’s impossible not to connect rising dues with high officer salaries. In 2004 President Donald Doser pulled down a whopping $807,626 in salary and allowances, making him the highest paid official in the entire labor movement that year.

STAYING LOCAL

In the face of a steadily shrinking labor movement, many of the nation’s biggest unions have increased their reliance on centralized national funds for organizing, coordinated bargaining in key industries, and political action. SEIU’s six-year-old “Unity Fund,” which pools more than $75 million a year, is the most prominent example. Last year AFSCME, CWA, and the Laborers all adopted similar programs and dues increases like those reported in Table 1 are increasingly channeled towards these strategic initiatives.

It’s important, however, given all this attention to changes at the national level, not to lose site of what is happening at the base. More than 70 percent of all dues collected in today’s labor movement stay at the local level, and local unions are where the rubber meets the road—whether it’s organizing new workers or defending the wages and benefits of existing members.

Even SEIU, which pioneered large-scale centrally coordinated programs, started their organizing push with the 1996 10/15/20 plan—where local unions eventually shifted 20 percent of their budgets to new organizing. In many unions, the commitment to using local resources strategically dates back even further.

Speaking of his union’s recent victory over San Francisco’s Multi-Employer Group, the business association representing 13 of the city’s major hotels, longtime UNITE HERE Local 2 member Jon Palewicz commented, “This really started more than 20 years ago, when we decided to make our local an organizing union. We voted to set up an organizing fund, in addition to our strike fund, and to create a separate organizing department.”

Palewicz continued, “Without those resources we couldn’t have organized the Marriott or won our last contract fight.”

While discussing the local’s $10 per month strike assessment, Palewicz was quick to echo the concern of many rank-and-filers when it comes to dues: “I’ve always said that we have to be as concerned with how we spend the money as how we get it. It’s like a see-saw--you have to pay attention to both ends.”